A talk by Jonathan Cobb, Historian and Author on the Republican Era in British History was held on 16th November 2023 at the Maitlandfield House Hotel, Haddington.

He studied History at Edinburgh University. He then held a commission in the British army until 1988, after which he pursued a career in investment management. He was awarded the Ministry of Defence Bertrand Stewart Award in 1988 for a work on the strategic challenges posed by the USSR and China, and was awarded the Bloomberg/Daily Express International Fund of the Year Award in 1997. He lives and writes in East Lothian.

The following is a precis of his talk:

Based on material in his book ‘A Sword for Christ’, Jonathan Cobb guided us through the complexities of the turbulent and bloody period between 1641 and 1660. The preceding Bishops’ Wars in Scotland, the English civil wars, the Irish rebellion and the Anglo-Scottish war of 1650-1651 constituted the Wars of the Three Kingdoms at the conclusion of which Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate was established to extend the republicanism of England to the rest of Britain. Jonathan wanted to highlight the role of Scotland in these developments.

The prime driver of these events was religion. Charles I wanted to unify ecclesiastical structure and governance throughout his kingdoms with himself as head. In Scotland he attempted to force the adoption of the Anglican episcopal system through the introduction of bishops. This did not sit well, to say the least, with the Calvinist presbyterian Scots. Matters came to a head with the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer as part of church service. The resultant public unrest and refusal to accept this imposition led to the National Covenant of 1638 in which signatories agreed to defend the precepts of the Kirk This led to the Bishops’ Wars in 1639 and 1640 in which the Covenanter army faced down and defeated the king’s forces, with the result that Charles backed down and Presbyterianism was confirmed north of the border. However, it is an important point to note that while the Covenanters were against Charles at this stage, they were never against the monarchy as an institution. Under the de facto leadership of the Marquess of Argyll the Covenanter Scottish government eventually offered alliance with the parliamentarian faction in England.

In the meantime the royalist cause in Scotland was led by James Graham, Marquess of Montrose, a very able general who caused serious problems for the Covenanters with a number of remarkable military victories. This Scottish civil war ended with defeat for Montrose at Philiphaugh in 1645 and his eventual capture and execution.

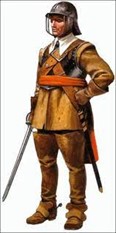

Victory in the Bishops’ Wars could be interpreted as the first way in which the Scots influenced events in England, at least partly for the following reason. Parliamentarians had come to resent the autocratic Charles, which generated dissent in large measure. Taxation was part of this, and the fact that Charles had prorogued parliament and attempted to rule by royal prerogative since 1629. Combining this with the significant representation of puritans and other non-conformists within the parliamentary group, and their supporters at large, the Covenanters success lit the powder keg and the First Civil War broke out in 1642. The Scots supported the Parliamentarians and the two parties signed the Solemn League and Covenant in 1643. This offered military assistance in exchange for the establishment of the Scottish presbyterian system in England. At this time Scotland, although with small population of only about one million, was a significant military power able to raise a substantial army. It contained among its forces many highly experienced professionals who had fought in Europe for the protestant side in the 30 Years’ War. Among them were Alexander Leslie and his kinsman David Leslie. Alexander was commander of the combined covenanter and parliamentary forces at the Battle of Marston Moor, a major victory following which the royalists conceded the north.

This victory was marred by later failures on the part of the parliamentary army. The consequence of this was the agreement by parliament to authorise the formation of a standing army in 1645 – the New Model Army. Led by Sir Thomas Fairfax, the army routed the royalist forces at the Battle of Naseby in June of that year, and further reverses led to Charles’ surrender to the Covenanters at Newark in the spring of 1646. The Scots then took the king north to Newcastle.

Led by the Marquess of Argyll there followed a period in which the Scots tried to get Charles to sign the covenant and eject bishops, and agree to the presbyterian model in England as well as Scotland, which he refused to do. After much wrangling the Scots gave up and Charles was handed over to parliament. Negotiations continued at Hampton Court, Charles dissembling and delaying in the hope that he could reassert his authority, but all to no avail. The result in 1648 was the Second Civil War which ended with defeat for Charles, and his subsequent execution.

For political reasons too complex to go into here, in 1648 the Scots sent an army in support of the royalists. These were the ‘Engagers’ (prepared to negotiate further with Charles) but did not have the support of the Covenanters, certainly not Argyll. Defeat by the New Model Army followed at Preston under the command of Oliver Cromwell and John Lambert. The Scots were later horrified by the execution of Charles and, through the Treaty of Breda in 1650, agreed to have his son Charles, Prince of Wales, crowned Charles II, in Scotland.

By now it was clear that the English had no intention of honouring the Solemn League and Covenant and the Scots decided to fully support Charles, then still Prince of Wales, when he agreed to sign the Covenant. England was now a republic, or Commonwealth, governed by the Rump Parliament. In 1650 the New Model Army was engaged in suppressing the Irish revolt, but Crowell led part of it back to Scotland to pre-empt any attempt by the Covenanters to invade England. He inflicted a crushing defeat on the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar after which Scotland’s political independence began to wane. In 1651 the Scots crowned Charles king, the crown set on his head by Argyll at Scone, and then sent an army south to try and overthrow the Parliamentarians. A disastrous defeat at Worcester ended the royalist hopes. Charles escaped to Europe and Scotland was essentially prostrate before the forces of Parliament.

Subsequently, the Scottish Parliament was dissolved and Scotland forcibly united with England in a common republican polity. In 1653 this became the Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell. On Cromwell’s death in 1658 his son Richard became Lord Protector for a short period, before the final collapse of the republican model with the Restoration of 1660, Charles II ascending the throne. Argyll presented himself at court in Whitehall, but was arrested, accused of treason, returned to Scotland for trial and executed in 1661.

In conclusion, the Scots had an important role in the attenuation of Charles I’s authority, were then appalled by his execution and fought for his son before finally being absorbed into a republic they never wanted. At least Scottish Presbyterianism survived as a national institution, but variations in religious practice were now permitted, except for Catholicism.

Peter R Nov 2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.