Dr Alison Rosie of the National Records of Scotland spoke on this topic. She dealt comprehensively with the inventories and their contents, outlining the principal jewels and textiles, their composition origins and significance, and potential beneficiaries.

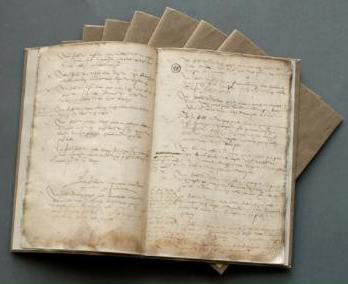

In early June, 1566, the heavily pregnant Queen Mary prepared a will of which two copies were produced. None now survive. However, the associated inventories of valuables had languished in Register House unrecognised until their discovery in 1854. This testamentary inventory is annotated in French by the Queen herself, a treasure held in the National Archives of Scotland, now the National Records of Scotland. Poor storage conditions in the past resulted in significant fading and damage to the papers. However, in 1863 Joseph Robertson published transcripts when the writing was more legible. These are now of great value and include a full page originally in the Queen’s own hand. The inventory was divided into two ‘gatherings’, the first listing items of greatest value and signed by the Queen and by Mary Livingston (a Lady in Waiting), and the second signed by the Queen and Margaret Carwood (a Maid of Honour).

There were 253 entries in the inventory – note that an entry could represent a number of jewels, not just one item. The list included hat jewels (ensigns or hat badges), necklaces, pendants, pearl necklaces, jewelled girdles, scented pomanders and pomander beads. The last were to mask the smells of the somewhat unsavoury city environment of the time, and to create a zone of pleasant air immediately around the body and so reduce the effects of disease-causing miasmas. Other items included bracelets, earrings, gold and pearl buttons, serpent’s tongues and ‘unicorn horn’. The last two (serpent’s tongues were bejewelled fossilised shark’s teeth; unicorn horn was some kind of non-mythical horn set in gold) were believed to protect the wearer from poisoning, an ever-present threat in the Renaissance court.

Sable (black or dark brown silky fur, of the eponymous animal) in the form of cuffs, scarves and other such, was hugely valued in medieval and early modern times for reasons associated with fertility and protection for the unborn child. The sables were listed in Mary’s inventory. Included were some with the animal’s claws still present, capped in gold. Associated with the fur were richly jewelled facsimiles of Sable heads – zibellini. The Sable (Martes zibellina) is a member of the weasel family of which, at the time and for unfathomable reasons, females were believed to conceive through their ears (but presumably gave birth in the usual way). The twist on this is that aural conception was linked to the immaculate conception of Roman Catholic belief, and Mary would have worn zibellini in this context as protective amulets for her pregnancy.

The jewels were set in gold and silver, some of Scottish origin, often with enamels. The gemstones included diamonds (from India), sapphires (from Sri Lanka), rubies (Myanmar), emeralds (Alps and Colombia), turquoise (Iran and Sinai), pearls (marine and Scottish freshwater), garnet and peridot. Faceting when present was relatively simple – mostly ‘table cut’ – and many gems were simply polished into spheroidal forms (cabochon).

The quantity and quality of jewellery was a visible measure of power and status, a ‘war chest’ to finance emergencies, and a resource for political gifts, and gifts for relatives, friends, and favoured servants at all levels. Gifts were always carefully matched to the status of the recipient and to the quality of any service. Hence the bequests in the inventory, with the proviso that in the event of Mary’s death and the survival of a son, all should go to the son.

Certain items belonged to the Crown and these were set aside.

The majority of beneficiaries were women, including Mary of Guise and members of the Guise family in France, Mary’s ladies in waiting (Mary Seton, Mary Beaton, Mary Livingston and Mary Fleming) and female aristocracy including the Countess of Argyll, and many more.

The principle male recipient would be her husband Henry, Lord Darnley, this despite his role in the murder of Rizzio. Clearly Mary felt sufficiently bound by protocol to overcome her detestation of Darnley. Other important beneficiaries were her half-brothers: James Stewart, Earl of Moray and Sir Robert Stewart of Strathdon (eventually 1st Earl of Orkney).

A shorter version of the talk earlier this year can be found on Youtube: at A Queen’s Jewel Box: The 1566 inventory of Mary Queen of Scots’ jewellery – YouTube.

You may also be interested in a blog post by Dr Alison Rosie that she wrote at the time of the release of the film “Mary Queen of Scots” : From the NRS Archives: Mary, Queen of Scots (1542-1587) – Open Book (nrscotland.gov.uk)

An interesting news item regarding a silver casket belonging to Queen Mary and bought by the National Museums of Scotland is to be found here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-61494813

You must be logged in to post a comment.