20th November 2025, 7.30 pm at the Holy Trinity Church – Professor Sara Lodge.

In a very entertaining and informative talk, Professor Lodge explored the myth and reality of the Victorian female detective. Her review in 2012 of two books first published in 1864 – The Female Detective and Revelations of a Lady Detective– piqued her interest. Following extensive research in newspaper archives and other sources Sara showed that, contrary to general opinion, there were many female ‘detectives’ and detective agencies run by women during the Victorian period. Their roles included working with the police or with private ‘enquiry’ agencies. In addition, theatrical melodramas and other fictional material with heroic lady detectives were very popular with the public.

Police Assistants

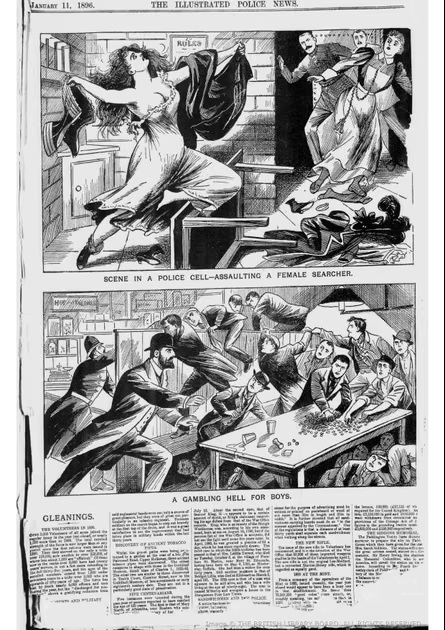

While there were no female police constables until 1917, women had been employed in significant numbers by the police. This could be short term or much longer. They were referred to as ‘female searchers’ or ‘female detective searchers’ and their roles were those which men could not with propriety undertake. This included frisking female suspects for small stolen items, or more intimate body searches. The detectives would search for items concealed in the voluminous clothing typical of the time (bustles, for example), or even in the hair. Frequently, stolen items were pawned and the pawn ticket retained and hidden for later redemption of the goods. A French suspect, for example, had no less than 45 pawn tickets hidden in her chignon! Other searches included examining the body for bruising and other violations in domestic abuse cases and providing this as evidence in court.

A more overt detective role could be seen from time to time. For example, Elizabeth Joyes in 1855, working out of Shoreditch Police Station, apprehended a thief who specialised in stealing luggage from the well-off in railway station First Class lounges. On one of her surveillances she spotted a man who, although otherwise appropriately dressed for a First Class passenger, was wearing very down at heel shoes. Bang to rights!

Women were frequently used in ‘sting’ operations, for example to identify and arrest back street abortionists. While this work could be dangerous, it was often poorly paid or even unpaid. (A Chief Inspector in Bradford used his wife for work of this kind!).

In 1888 the Whitechapel murders caused a sensation. The search for Jack the Ripper was undertaken by Scotland Yard which, at the time, had only 15 detectives. Despite sterling work including cross-dressing as women of the street to act as bait, they were hopelessly overwhelmed by the work. At the time Frances Cobbe wrote to the newspapers extolling the benefits of women as detectives in these circumstances. A predictable backlash wondered how virtuous women could retain their virtue working these mean streets! No women were employed for this case.

Private Agencies

Following the passage of the Matrimonial Causes Act into law in 1857 it became possible to obtain a divorce without recourse to an Act of Parliament which only the rich could afford. From being, in law, a part of her husband’s property, women were now able to exert some agency in the marriage. The system was still biased in favour of men – a man could obtain a divorce citing adultery only whereas a woman required evidence of adultery aggravated by, for example, desertion, domestic abuse and so forth. Gathering evidence for divorce cases became one of the main roles of the lady’s enquiry agencies which grew rapidly in number during the later 19th century. It was relatively easy for female detectives to get undercover employment as domestic staff, or as lodgers or barmaids where they could quietly pursue their enquiries without suspicion. A man would not be able to do this as easily. The main clients for these agencies were women.

An interesting local example of this kind of detective work involved the residents of Coulston House, Haddington, in the 1890s. William Hamilton Broun and his wife Lady Susan Broun Ramsay felt that some person (or persons) in their household was responsible for a number of disturbing, unexplained events – rat traps being sprung, eggs smashed in the henhouse, ponies being moved from field to field, one dying as a result of an injury, post being tampered with and difficulty in hiring/retaining staff. The Brouns engaged the London Agency of Steggles and Darling to investigate. Accordingly, one Clara Layt, a lady detective, was employed as linen maid. Over a month or so she was able to look into the situation in the household through conversations with fellow staff and with folk in Haddington. By great good fortune the many short reports she sent to her employers have been preserved and are held in Register House, Edinburgh. They show that all she uncovered was dissatisfaction among the staff because they were not being paid regularly, and scandalous rumours about her Ladyship. That Lady Susan was probably showing physical signs of syphilis suggested to the rumour mongers a dissolute early life replete with lovers. Sadly, the lack of virtue applied not to her but to her ex-husband Robert Bourke, a philanderer with many extramarital partners and the probable source of Susan’s STD.

Thus, Clara Layt was unable to identify a culprit, for which reason Broun refused to pay the fee. A subsequent court action brought by Steggles and Darling to recover their fees and expenses was found in their favour, but not to the full amount claimed. Sadly, during the trial Lady Susan died, presumably from syphilis.

Clara Layt was in reality Clara Jolly Death, the wife of Leonard, a detective – a memorable surname perhaps best concealed in Clara’s undercover work.

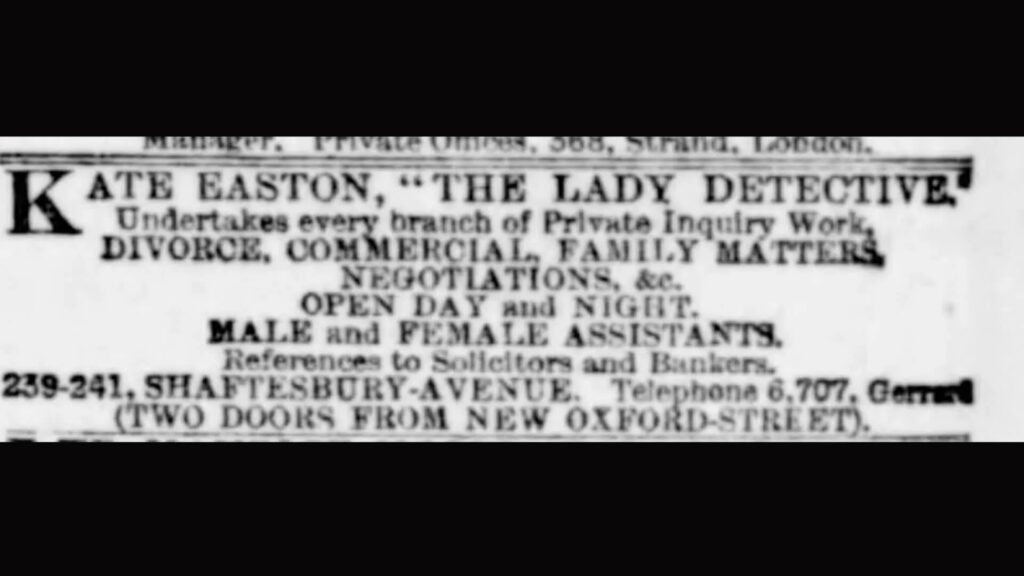

Among the well-known detective agencies were those of the gun-toting former actress Kate Easton with premises in Shaftsbury Avenue, and of Antonia Moser nearby.

Both women were suffragists if not suffragettes and both published lurid semi-fictional memoirs in the newspapers. The latter were important means of advertisement to help them survive in the highly competitive market for enquiry agencies in London at that time.

Theatre

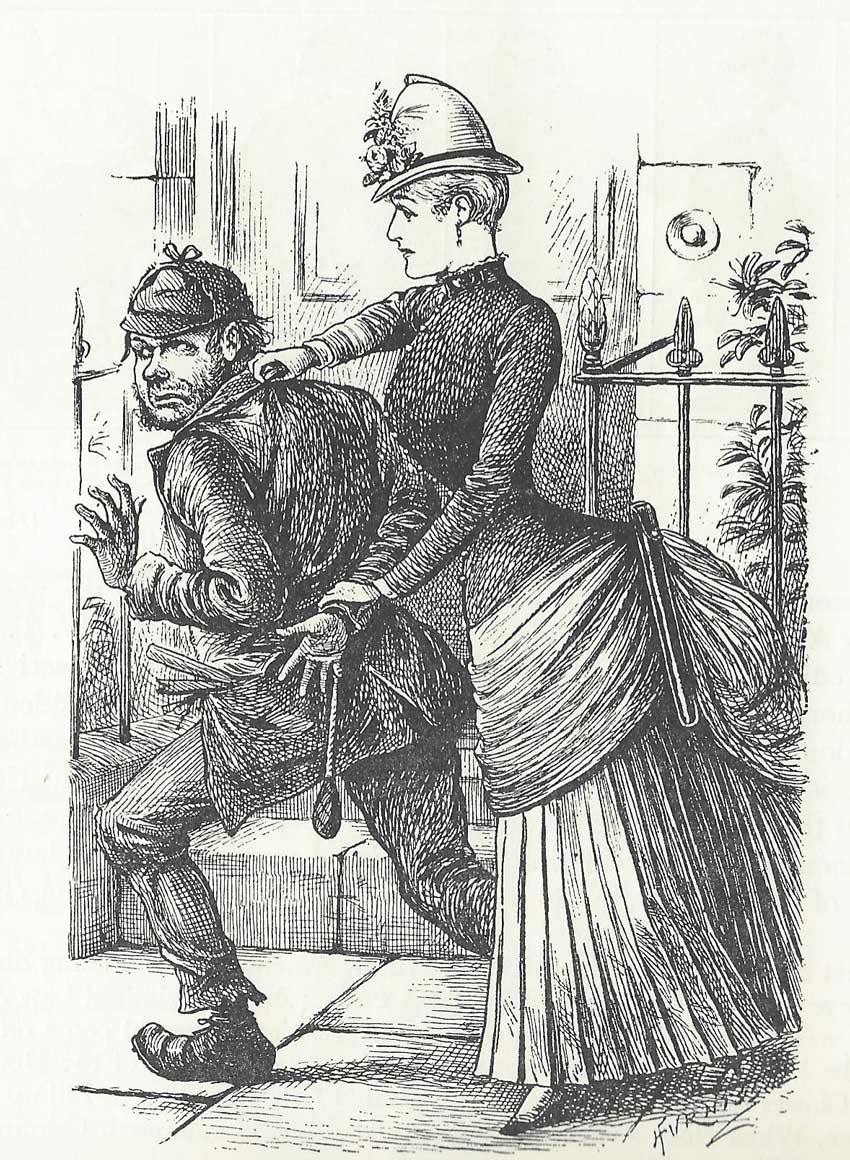

The more sensational activities of lady detectives were not lost on a Victorian public hooked on melodrama and penny dreadfuls. Indeed, many plays were written around the exploits of lady detective heroines, perhaps exaggerated somewhat from newspaper accounts of the more dramatic/salacious real cases.

The idea of a brave, clever, sometimes cross-dressing woman solving a crime in the most melodramatic of circumstances sold tickets in the thousands. For example, Dorothy Tempest, a detective-come-playwright, wrote and starred in the 1864 play The Female Detective. She played 5 or 6 parts of all ages and genders in a Britannia Theatre production. The theatre capacity was 4500!

The actor/manager of the Britannia from 1871 was Sara Lane who ran the theatre successfully for many years, becoming a great favourite of her theatre going public. As well as music hall and pantomime productions, detective plays featured frequently in her programmes. Sara was known as the Queen of Hoxton and when she died her funeral was a huge affair, with mourners lining the streets as her cortege passed. It was the largest turnout for a funeral in London seen up to that time, bested only by that for Queen Victoria a few years later.

To summarise, then, what is known about the myriad female investigators of the time, most were working class, often mothers, generally working with the police or employed by agencies. The work was usually undramatic and routine, often with employment conditions similar to the modern zero hours contracts, although rates of pay and employment periods were quite variable. For example, Ann Lovsey had a career lasting 36 years as a searcher with the Birmingham police. Most work was far removed from the sensational or dramatic seen in very occasional real-life investigations or in the ubiquitous theatrical melodramas. Most work with private agencies concerned marital misbehaviour. The value of working class women was that they were streetwise, could blend in easily with target groups or people and, as we have seen, could readily go undercover as domestic servants or assume other female working roles. With these advantages information could be surreptitiously gathered.

Peter R

24 Nov 2025

You must be logged in to post a comment.