4th September 2025, 7.30 pm at the Holy Trinity Church – Dr Rebecca Jones Keeper of Scottish History and Archaeology, National Museums Scotland

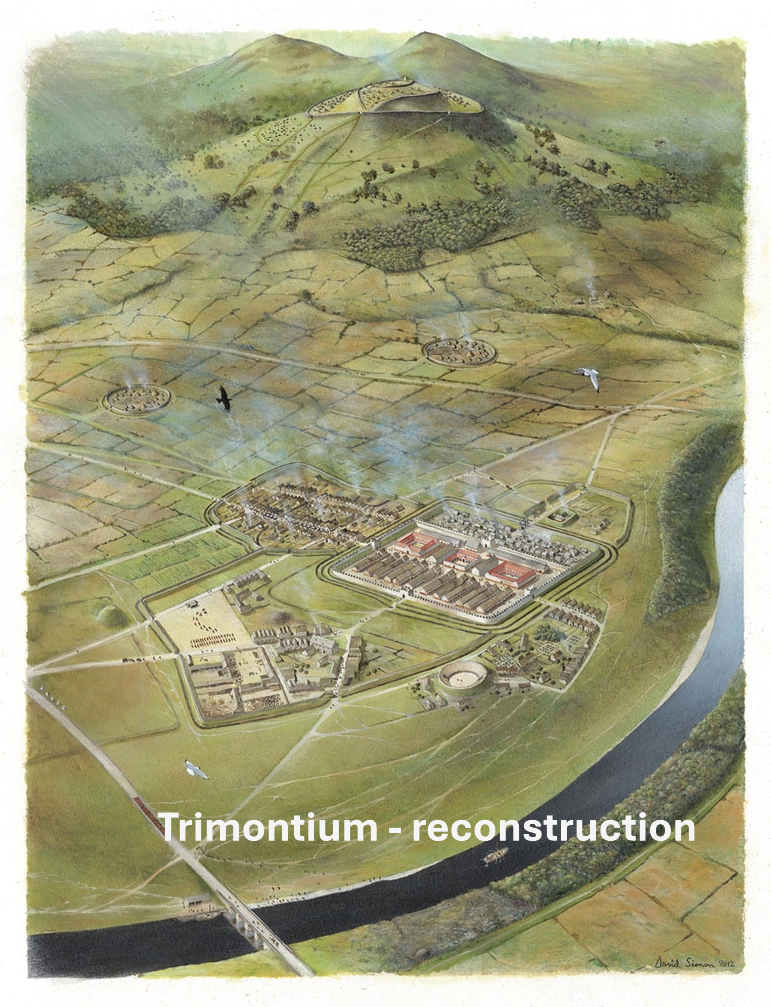

Dr Jones treated her audience to a wide-ranging and entertaining review of attempts to stabilise and then include Scotland within the settled Roman Empire. Late Iron Age life evidenced by archaeological study reveals round houses, brochs, crannogs and hill forts, which speak of tribal societies in settlements not very different from those of the rest of Britain. Much of the southern half of Britain, although by no means all, was under Roman control by the time Vespasian was raised to the purple in 69 CE. He and his sons Titus and Domitian, who respectively succeeded to the throne, comprise the Flavian dynasty and it was through their policies that Rome extended its power briefly to its furthest extent in Scotland. Having stabilised the north of England, the military governor Agricola led a successful campaign in Scotland (77/78 – 84 CE). The huge fort at Newstead by the Tweed (Trimontium), the fort at Elginhaugh near Dalkeith and the construction of several Roman roads, in particular Dere Street (roughly followed by the A68 nowadays), belong to this period.

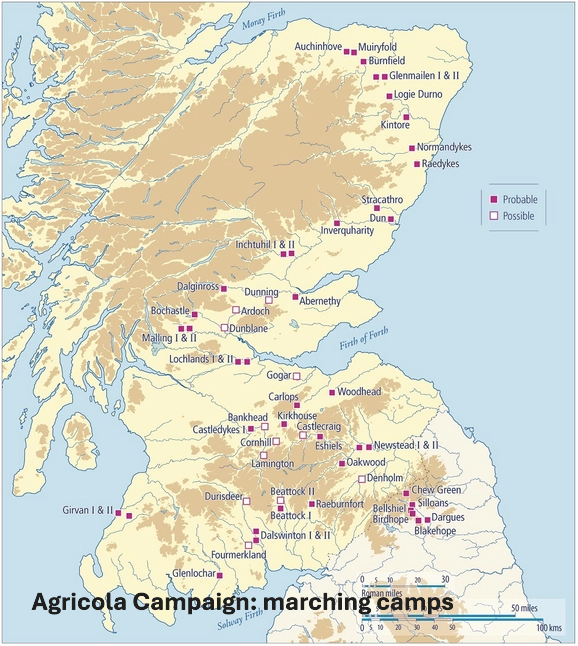

These military activities required a range of forts and camps of various sizes, the sites of many of which are scattered across much of Scotland. Indeed, the concentration of Roman military sites in Scotland is greater than anywhere else in the Roman world. There were Legionary forts like Trimontium, large and intended to be permanent, to accommodate around 5,000 soldiers and support; Vexillations which were temporary but well-built and accommodated about half of a legion or around 4,000 auxiliaries; Auxiliary forts accommodating 480-800 men; Fortlets (like the Milecastles on Hadrian’s Wall) accommodating 30-100 men, signalling stations and marching camps. Although varying in area from large forts like Trimontium of many acres in extent to small fortlets, the design features of the forts and marching camps were similar – basically a rectangular area surrounded by protective banks and ditches. Marching camps were the temporary camps of a campaigning army of which there is evidence of over 200 in Scotland. Some were very large indeed, the largest accommodating around 40,000 soldiers during the Severan invasion at the beginning of the 3rd century.

Agricola advanced from southern Scotland around the southeast/east edge of the Grampian mountains well into Moray, reaching as far as Cawdor. Logistical support relied heavily on a Roman fleet which sailed up the east coast. Fortifications over this 4-year period, including Ardoch, were constructed along the Gask Ridge, just west of Perth, and eventually an extended line of fortifications followed the route north as far as Stracathro. These represent what is believed to be the first defended frontier line in Scotland. The fort at Inchtuthil, between Perth and Blairgowrie, was very large indeed but was not completed before its abandonment in 86 CE. It was investigated by archaeologists in 1901 and more extensively over the period 1952-65, a notable find being a cache of over one million nails! Clearly the Romans had intended to expand accommodation in the fort, but orders to withdraw from Scotland intervened. Trouble on the Danube required large troop reinforcements.

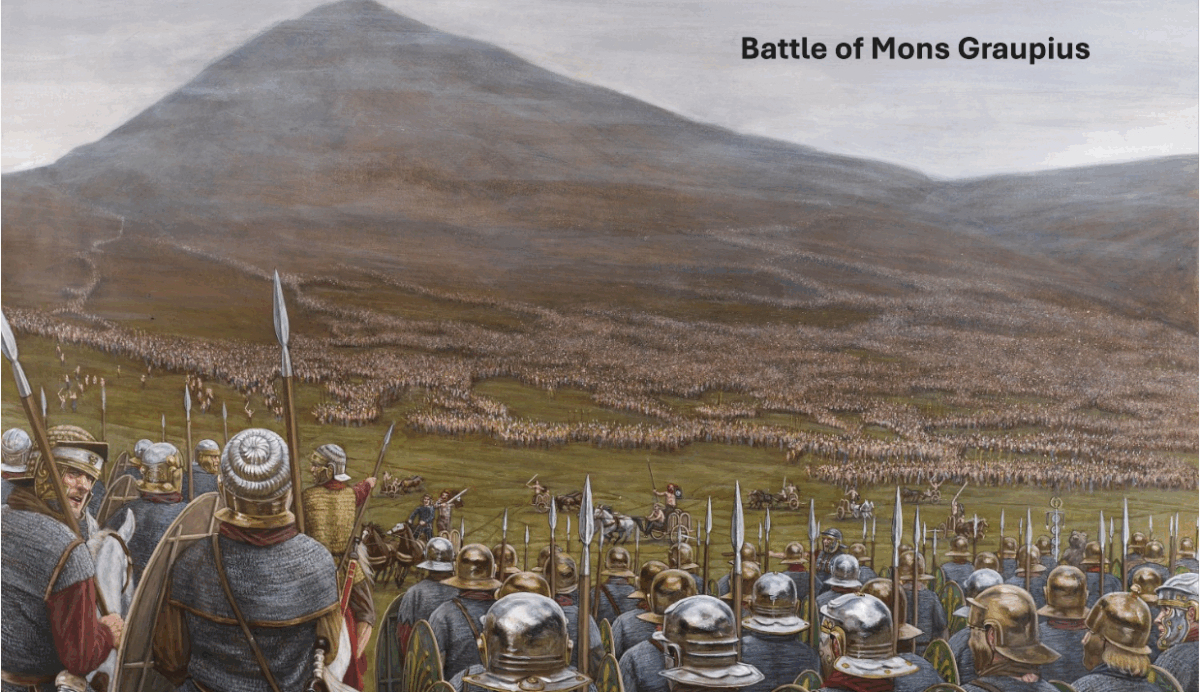

Agricola was the most successful of the Roman commanders in the Caledonia campaigns. According to a biography written by his son-in-law Tacitus, Agricola tempted the Caledonians led by Calgacus to a pitched battle in which the Romans routed their opponents. The site of the battle, Mons Graupius, has long been debated with a number of candidates proposed. A location in north-east Scotland (eg. Bennachie in Aberdeenshire) is thought to be most likely. However, following Agricola’s recall by emperor Domitian and the departure of legions for Europe, the Romans withdrew from Scotland to a ‘borderline’ between the Solway and the Tyne – the Stanegate – and one of the main forts they built then was Vindolanda.

Continuing incursions by northern tribes created problems until the completion of Hadrian’s Wall in the 120s CE. Hadrian’s policy of containment involved setting clear frontiers for the empire and in the case of his province of Britannia he ordered the construction of a wall along the line of the Stanegate to establish the northern frontier. There would still have been forward bases north of the wall and trade with the inhabitants. Tribes such as the Votadini in the Lothians and Berwickshire appear to have been happier than others to coexist peacefully with Rome over an extended period.

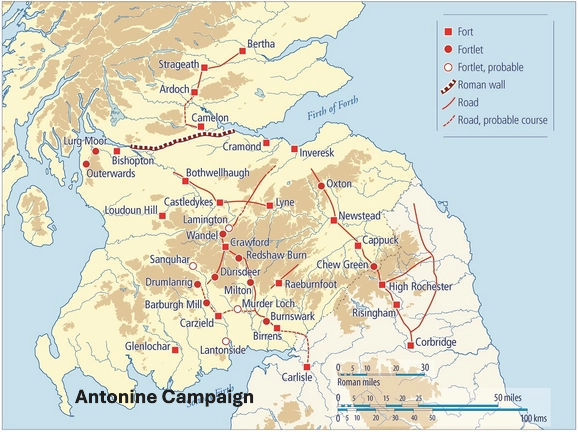

Antoninus Pius succeeded Hadrian in 138 CE and decided to push north once again to pacify this troublesome area. He appointed Lollius Urbicus, another very competent military commander, as governor of Britannia and set him the task of subduing lowland Scotland. Urbicus redeveloped Trimontium and built a new fort at Inveresk. His soldiers also redeveloped Ardoch on the Gask Ridge and built a series of small forts in Nithsdale and Annandale, all to discourage attacks by restive tribal groups.

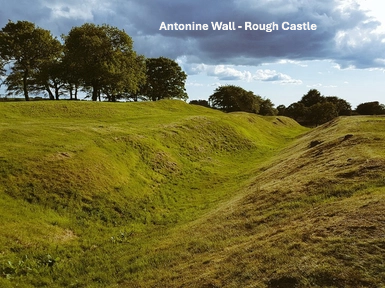

Meanwhile from 142 CE the Antonine Wall was constructed between the Forth and Clyde. Although only a wall of turf with protective ditches, it was nevertheless well built on a good stone foundation, and it created an easy to defend fortified border. However, it was abandoned after about 20 years and the Romans withdrew to Hadrian’s Wall.

For a period from the 180s CE to the end of the century there is little evidence of a sustained Roman presence in Scotland, but troublesome raids by the northern tribes were a persistent problem. Hence a third, and last, major campaign to pacify this northern extension of Britain and incorporate it into the Roman empire was led by emperor Septimius Severus. A full-scale invasion began in 208 CE with probably the biggest army yet seen in Britain – some 40,000 men. Huge granaries were constructed in South Shields and Corbridge, and possibly Carlisle, to support it. The army was led personally by the emperor and his two sons Caracalla and Geta. A base was constructed in Carpow, Fife, and the fort at Cramond re-established. In the end, however, the campaign was unsuccessful: guerilla tactics by the Brittonic tribes in a war of attrition significantly hampering the progress of the Roman army. Clearly, the lessons of Mons Graupius had been learned – a pitched battle against Roman legions would have been a bad idea! The death of Severus in York in February 211 brought a swift end to the campaign: Caracalla returned to Rome as emperor and the Roman armies withdrew to Hadrian’s Wall once again.

There is little evidence that Rome showed any further interest in Scotland other than to maintain its frontier by a combination of diplomacy, trade, bribery and short punitive raids from bases near Hadrian’s Wall. For example, there is some limited evidence of smaller campaigns in the later 3rd and 4th centuries, and we must account for the 5th century Traprain Hoard. The hoard was payment in cut silver plate from the Romans to the Votadini, probably over several generations, perhaps in return for their cooperation in maintaining peace of sorts. The Romans had probably surmised that the costs of another major invasion far exceeded any benefits.

While the Scottish Roman sites are invariably military, there was a significant civilian presence in association with Trimontium and Inveresk among others. This included soldiers’ families, artisans, traders and other civilians from a wide range of provinces in the empire. A wealth of artefacts reveals much about daily life in the forts and that soldiers came from places as far afield as Spain, eastern Europe, Syria and North Africa, as well as Italy. This is seen in the variety of pottery styles, for example tagine-like cooking pots indicative of North Africa. The soldiers’ diet seems to have been predominantly vegetarian, although many were infested by intestinal worms (evidence from excavated latrines) suggesting their diet was supplemented by meat. While pieces of clothing, military and domestic equipment, coins and jewellery give important clues, they do not have the impact of written material. In this context tombstones, altars and other inscribed stone fragments have been excavated and, when their inscriptions are legible they are very revealing. For example, one excavated near the Antonine wall, probably associated with the Auchendavy Roman fort, is inscribed with the name Salmanes, the son of Salmanes, likely a trader from Syria. Also from Auchendavy is a fragment of a tombstone for a woman called Verecunda, interpreted as that of a well thought of local woman or slave who may have been the partner of a soldier or official.

From the large civil settlement at Inveresk an altar stone dedicated to the god Mithras and another to Sol both dedicated by the centurian Caius Cassius Flavianus, reflect the religious life of the soldier. The stone lioness biting into the head of a captive barbarian dredged up from the Almond estuary at Cramond is a striking example of an ornament which would been set to guard the tomb of a high-ranking personage.

In conclusion, while very comprehensive, Dr Jones had time only to outline the history of the Romans in Scotland and the rich trove of military sites and artefacts they have left behind. I hope this summary has given something of the flavour of her fascinating talk.

Peter Ramage, Sept 2025

In terms of online resources, Dr Jones is writing a general book on Roman Scotland but in the meantime has provided links to some great online resources – notes, blogs and films.

Romans in Scotland: major archaeological sites | National Museums Scotland

Romans in Scotland: life on the frontier | National Museums Scotland

The Romans in Scotland in five objects | National Museums Scotland

A brief history of Roman Scotland | National Museums Scotland

The Roman army in Scotland | National Museums Scotland

Plus a few blogs which may be of interest:

https://blog.historicenvironment.scot/2017/10/scotlands-african-emperor

Your members may be interested in a feature length film that was made for the Antonine Wall:

And a project based short one on the Antonine Wall which is one of a series, but this is the general overview:

You must be logged in to post a comment.