20 March 2025, 7.30 pm at the Holy Trinity Church – by Peter Raine, Paediatric Surgeon

This evening’s talk by retired consultant paediatric surgeon Peter Raine dealt with the life and career of the prominent Victorian surgeon Sir William Fergusson.

Fergusson was a son of East Lothian, born in Prestonpans in 1808 during the Napoleonic Wars and within living memory of the Jacobite rebellion and Battle of Prestonpans in 1745. After early school life in Prestonpans, he moved with his parents to Lochmaben near Dumfries from where he was boarded at the Royal High School in Edinburgh.

He was a very intelligent and talented boy, having learned to play the violin at an early age and developing significant woodworking skills – both carpenter and carver – all of which he carried forward to later life. Fergusson initially thought to follow his elder brother into the law but after 2 years decided it was not for him and matriculated at Edinburgh University Medical School. He came under the tutelage of Robert Knox, surgeon and leading anatomist of the time, and impressed his supervisor so much that in 1828 he was appointed Demonstrator in Knox’s anatomy school and soon became Knox’s chief assistant. His intricately dissected arterial system of the foot, presented to Knox and still on display at the Royal College of Surgeons, is testimony to his skill. At this time, Knox’s anatomy school was by far the most popular of several in Edinburgh, with average class sizes of 335, and in 1828/29 a class of 504. Knox was a brilliant anatomist but combined this with a dogmatic, forceful and arrogant personality. Nevertheless, Fergusson worked hard and well with him and became a very accomplished anatomist himself.

At this time, obtaining sufficient bodies legally for dissection was difficult, controlled as it was by the Murder Act of 1752 in which only executed murderer’s bodies could be freely used. Having several independent anatomy schools competing for the limited supply of subjects, to meet demand a clandestine, lucrative and illegal trade in the recently deceased became established. Bodies were exhumed at night, delivered to the ‘back door’ of the anatomy school and payment made to the procurers. The suppliers became popularly known as the ‘Resurrection Men’, ‘Resurrectionists’ or just plain body snatchers and grave robbers. Attempts to curtail these activities resulted in watch towers in some graveyards, and mortsafes to prevent access to the graves.

William Burke and William Hare took a new approach to the business: supplying corpses of people freshly murdered by them, this at the time Fergusson was working with Knox. When the depredations of Burke and Hare were uncovered, Knox’s reputation was severely tarnished but Fergusson evaded censure in part due to a death cell statement by William Burke which, incidentally, also cleared Knox of direct culpability:

“Burke declears that Doctor Knox never encoureged him, neither taught or incoriged him to murder any person, neither any of the assistants, that worthy gentleman, Mr Fergison was the only man that ever mentioned anything about the bodies. He enquired where we got that young woman Paterson because she would seem to have been well known to some of the students. Sined, William Burke. Prisoner.

Condemned Cell, Jan 21 1829”

To regularise the supply of bodies for anatomy, the Anatomy Act of 1832 stated that a body could be donated for dissection if it were in the lawful possession of the donor(s) and that no objections were raised by the family of the deceased. Also, it codified the legal use of unclaimed bodies.

Meanwhile, Fergusson’s career went from strength to strength. In 1829 he was elected Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS) of Edinburgh and in 1831 he became a surgeon in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. He married Helen Hamilton Ranken in 1833, a wealthy woman who “relieved him of any worries he may have had on finance”. He bought Spitalhaugh near West Linton which he retained for his lifetime. At the infirmary he worked with another famous surgeon, James Syme, until he left in 1840 to take up the post of Professor of Surgery at Kings College, London. There, Fergusson followed in the footsteps of Robert Liston, a famous surgeon renowned for his speed in performing operations, notably amputations. This was an essential skill, in a time before the advent of anaesthesia, to minimise shock to the patient and to maximise the chance of a successful recovery. There was also more than an element of showmanship to the successful surgeon’s trade.

Fergusson became a very skilled practical surgeon and espoused the idea of ‘conservative surgery’. For example, a damaged elbow or knee joint generally offered amputation of the limb as the easiest option, which was widely carried out. Fergusson developed techniques whereby the damaged joints could be excised and the limb at least preserved. This required the patient to be well supplied with whisky, rum or whatever spirit might be available to drug them into a stupor if not unconsciousness. Skill combined with speed was the order of the day. Fergusson kept notes of all his operations and published them in the 3-volume ‘A System of Practical Surgery’ (1842) where the emphasis was very much on ‘practical’. He also included them in a series of lectures entitled ‘Lectures on the Progress in Anatomy and Surgery in the Present Century’ (1867).

In Lecture #11 ‘Preservation of Limbs’, he describes excision of the head of the femur, knee joint and elbow joint. Elsewhere he describes the removal of bladder stones and, amazingly for the time, the removal of the maxilla (upper jaw) in cases of cancer. He became renowned for his success in treating cleft lip and palate for which he devised a range of special knives and hooks. His detailed anatomical insight guided his clever incision of certain muscles which made operations easier. Not only did he follow the mantra ‘speed is of the essence’, he advised an early return to feeding and speaking. Fergusson’s 300 or so operations of this type resulted in a mortality rate of about 5%, for the time remarkably low.

He planned his operations meticulously but replaced detailed explanations to his patients with a brief “We will do a little something”. He was generally completely silent throughout the procedures, to the extent that observers thought (wrongly) that he was on bad terms with his assistants. His concentration and focus on the details of an operation were absolute. An interesting fact at this point is that despite an early use of ether as an anaesthetic by Liston for an amputation, and familiarity with the anaesthetic effects of chloroform through his friendship with James Young Simpson, Fergusson did not favour the use of anaesthesia for his procedures.

It would be remiss to omit mention of his design of novel surgical instruments in addition to the knives and hooks mentioned above. He devised an instrument (lithotrite) to crush bladder stones in situ, rather less risky than the usual operation to access the bladder and remove the intact stone. Another instrument associated with him is the lion bone holding forceps he designed to assist in the removal of the maxilla.

Fergusson’s reputation was such that he was appointed surgeon-in-ordinary to Prince Albert in 1849. In 1855 he became surgeon-extraordinary to Queen Victoria. In 1866 he was made a baronet and in 1867 appointed sergeant-surgeon to the Queen – a high honour. In the early 1840s Fergusson was elected FRCS, in 1870 he became President of the Royal College of Surgeons and in 1873 became President of the BMA.

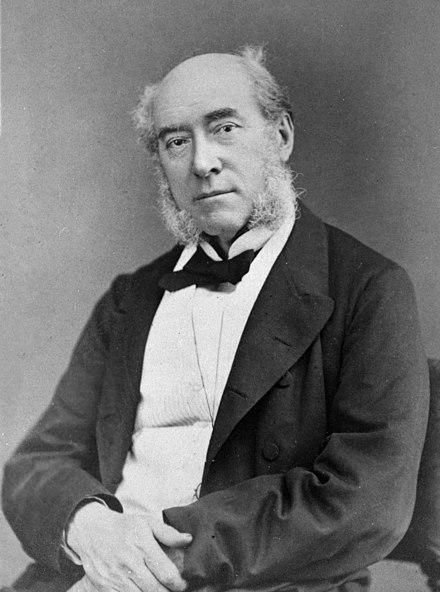

Fergusson was a tall imposing figure who, despite his single-minded, ambitious professional persona had none the less a considerate and friendly disposition. Always sociable, and very popular his flamboyant nature was displayed in his preferred mode of transport to his engagements around London: a bright yellow coach complete with two postilions and two well-trained dalmatians. He featured in one of the famous ‘Men of the Day’ prints in Vanity Fair.

Fergusson never lost his considerable expertise with the violin and carpentry. He was also an expert fly-fisher and lover of drama. In his final years he was frequently back at Spitalhaugh. Predeceased by his wife (1860) and his eldest son (1864) Fergusson died in London in 1877. To honour this very well-known and popular personage, around 2,000 mourners crowded the platforms at Euston station as his body was taken to Scotland for burial. Sir William Fergusson is buried with his wife in the graveyard of St Andrews Church, West Linton.

Peter R 24/03/25