24 April 2025, 7.30 pm at the Holy Trinity Church – David Weinczok, Historian, writer, presenter, museums professional and Canadian-born ‘New Scot’ based in Edinburgh since 2011.

The vast timescale, the large numbers and the many changes in style and purpose for the titular fortifications necessitated a broad-brush approach to give a comprehensive overview. In a well-illustrated talk, David Weinczok encompassed the hill forts of the bronze and iron ages; the Roman period of military forts and marching camps; the medieval period and the ‘golden age’ of castle construction and later tower houses; concluding with the evolution of less fortified or unfortified country houses in the late medieval and early modern periods.

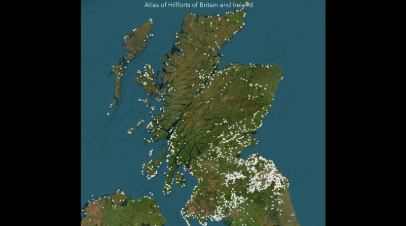

‘Hillforts’

In the broadest sense, hillforts are built-up enclosures ringed by earthen ditches and timber or stone ramparts, typically 3 or 4 (‘multivallate‘). They are, as the name suggests, often – though not always – located on raised ground, usually upon prominent crags, slopes, and volcanic plugs. Many line valleys and ancient thoroughfares, with wide-ranging views along. None now survive fully intact, and the vast majority have only the earthen ditches and occasional patches of tumbledown masonry to see.

Hillforts emerged in the Early Bronze Age around 2,500 BC, a time when many past generations of farming activity laid the groundwork for a slow but steady population increase and evermore specialised roles within communities. Some were occupied well into the medieval and even post-medieval period, though the majority seem to have been abandoned in the late Iron Age (late BC, to the Roman incursions of 1 st to 3 rd centuries AD). A flourishing of hillforts occurred around 1250-1000BC. This was a period of climactic optimum which saw less precipitation, overall warmer temperatures, and increased crop yields. During this period cultivation could take place up to around 400 metres above sea level, meaning that many hillforts could cultivate the land immediately around them rather than relying on the more fertile land below. A period of abandonment occurred in subsequent centuries which saw temperatures fall by nearly 2 degrees Celsius and an increase in rainfall. Growing seasons shortened, yields dropped, and many settlements even as low as just 250m above sea level had to be abandoned.

Though it’s natural to assume that hillforts were permanent settlements, some seem to have been occupied only seasonally. Some of the highest-situated hillforts may only have been occupied during the summer grazings, when a community’s cattle and sheep grazed on upland pastures before being brought back down to the permanent, lower-lying settlements. So, rather than thinking of hillforts as permanently occupied sites functioning like walled towns, many would have been ephemeral with the population living elsewhere in normal circumstances.

Much is made of the ‘fort’ part of the word ‘hillfort’, and yes, many hillforts did have substantial walls and multiple layers of earthworks to overcome. However, they were built in a period where large-scale warfare was extremely rare. Raids by neighbouring tribes, usually focused on procuring livestock, were the norm, and all you needed to do in that case was bring the people and animals inside the hillfort and wait it out. We know of no hillfort in Scotland being besieged on a large scale by other native peoples prior to the Early Medieval period. Not a single hillfort in Scotland attacked by the Romans proved capable of resisting them, so while they were places of power they could be fairly easily overcome by large, organised force of arms. In the south of Scotland, the Borders are the most densely spotted area for hillforts with over 400 discovered so far. Dumfries and Galloway and East Lothian are close seconds, each with dozens of known, extant examples. As with the later medieval castles, hill forts were established and then modified at intervals throughout their useful lives of many hundreds of years.

In East Lothian, the majority of the region’s hillforts line the northern and eastern lower slopes of the Lammermuirs. These afford sweeping views across the plains of the Lothians and the ancient coastal route via what is now Dunbar. A few are found in the lower ground in northern East Lothian. The most dramatic examples punctuate the towering volcanic plugs and crags, such as at Traprain Law and North Berwick Law.

The former was the capital of the Votadini people who lived in the Lothians throughout the Iron Age. However, like many other East Lothian hillforts its origins stretch at least to the Bronze Age. Traprain Law’s enclosed area covered around 30 acres and its ramparts stretched for over a kilometre, encircling the entire hilltop. These defences were strengthened immediately prior to the first wave of Roman invasions in the late 70s or very early 80s CE. The relationship between the Votadini and the invading Romans is ambiguous. They seem to have become a sort of client tribe, serving as a buffer zone against the more hostile peoples to the north. Whether they directly supported the Roman advance or merely stayed out of their way is open for conjecture. The Traprain Hoard of Roman silver is suggestive of client status. Traprain is a particularly large hillfort but those at The Chesters near Drem and White Castle high up on the Garvald to Whiteadder road are more typical. The latter preserves a very obvious circular multivallate form.

At White Castle over 25 circular foundations have been identified within its ramparts, and again the ramparts themselves were built and amended over many centuries. A scattering of Neolithic finds was made on the site, with other periods of activity dated to the Iron Age between 750-400 BCE and 366-100 BCE. It was also still in use during the medieval period, with structural remains dated to the late 10 th or early 11 th centuries CE and even one structure from as recently as the 16 th century.

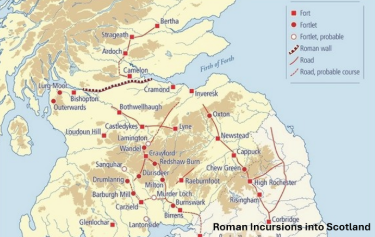

Roman Period

Roman works in Scotland are all military in nature. There are no countryside villas, no civitas, and no aqueducts. Only forts, fortlets, roads, and walls. Very little of the Romano-British culture which emerged in southern Britain is found in the north.

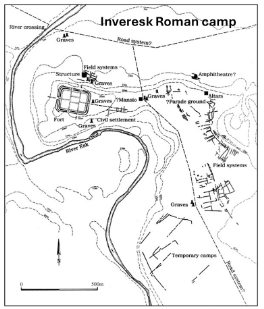

The only major Roman fort site so far identified in East Lothian is located within the grounds of St Michael’s Church in Inveresk. It was first discovered during the reign of Mary, Queen of Scots. The queen herself was aware of it, and an inscribed stone was presented to her but subsequently lost. This fort was established during the Antonine Period around 140 AD as the Romans re-established their hold on southern Scotland and abandoned by 165 AD during the same withdrawal which saw the disuse of the Antonine Wall. The fort was built first of clay and timber and then later of stone, again telling us that this was no mere staging ground but a place which was viewed as integral to the invasion efforts. Doubtless there are other Roman era remains to be found in East Lothian, but so far only Inveresk and the silver hoard given to the people of Traprain Law have been unearthed.

Medieval Period and Castles

Broadly speaking, a castle is the fortified home of a member of the nobility, military aristocracy, or royalty. Generally, they were designed to be the dominating central power base of the feudal lord in the area. Whereas hillforts often enclosed a significant proportion of a community’s population, castles marked a fundamental division between the rulers and the ruled. Only a tiny and relatively privileged number of people in a community would have had regular access to castles, whereas hillforts often functioned as fortified settlements with several hundred people.

Put simply, and bearing in mind all the tiny variations and disagreements about what makes a castle, a castle has to be able to put up a fight and also function as an elite home. Going by that definition, there are somewhere in the neighbourhood of 2,500 castles in Scotland. East Lothian boasts at least 100 of these, including some of the grandest and mightiest examples of their kind.

Castle building was a product of the feudal system, introduced in full into Scotland by David I in the 12 th century. Lands were conferred in feu by the king to nobles, most of whom at this time were of Norman families. The earliest castles were simple earth and timber affairs called Motte and Bailey castles – each essentially a mound of earth with a timber tower or Keep on top, the surrounding lower ground within a boundary fence to create the bailey. East Lothian contains one definite motte still obvious today. Known as Castle Hill, it stands in the East Links of North Berwick. There is some evidence that Yester Castle began life as a Motte and Bailey, a much-modified motte having the Goblin Ha’ built into it. Conjecture as that may be, many of the early castles were restructured in stone and were modified over the centuries in response to destruction, damage, and to the development of artillery.

The extended period of relative peace between England and Scotland during the later 12th century and most of the 13th , coupled with an extended warm, relatively stable climate (the medieval climactic optimum from about 1100 to 1300) gave ideal conditions for the construction of substantial stone castles requiring a decade or more to complete. This ‘golden age’ of castle building is represented by several important East Lothian examples.

Dirleton Castle

This is foremost among the Golden Age castles of East Lothian. The lands of Dirleton were gifted to the de Vaux family by William the Lion shortly before the year 1200, and there is reference to a ‘castellum de Dyrlton’ as early as 1225. When de Vaux built Dirleton a new type of castle was emerging, with curtain walls with high towers at their corners. Dirleton Castle’s donjon is the earliest confirmed donjon in Scotland. It stood 4 storeys high, although today only three storeys survive with the third being badly reduced. Dirleton also adopted a feature which since became synonymous with castles – a portcullis with a retractable drawbridge.

The area enclosed by the curtain wall nowadays contains the famous garden. Visiting Dirleton Castle today you see three distinct phases of building: the de Vaux donjon, the gatehouse and other buildings from the 14th -15th century and the southern range constructed in the 16th century. Like all good, enduring castles, there was no single mastermind behind it – Dirleton is the product of several centuries of occupation, architectural evolution, and experimentation. The castle was abandoned in the 1650s after the artillery of the Cromwellian siege rendered it unusable.

Hailes Castle

Hailes Castle overlooks the River Tyne just west of East Linton. It was first built by the de Gourlay family from Northumberland around 1200. This first castle was more of a fortified manor house than the sprawling castle you see today. Following the Wars of Independence the Hepburn family acquired Hailes and greatly expanded it to include a curtain wall, tower house, and chapel. It became one of the strongest castles in the Lothians, despite having higher ground immediately to the south.

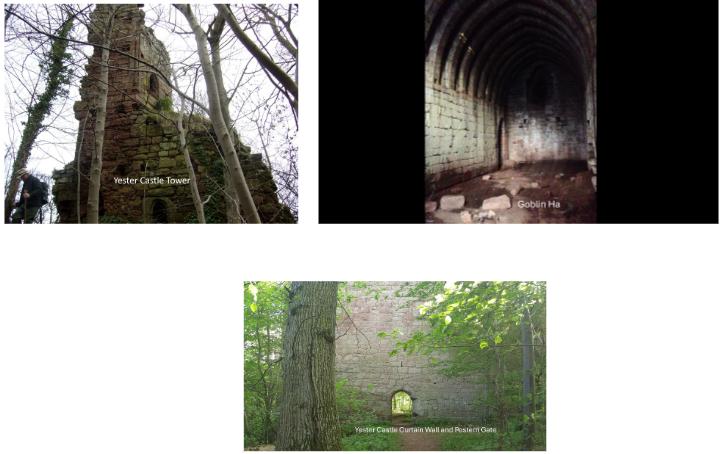

Yester Castle

The castle was built by the de Giffards in the first part of the 13 th century. Later that century the family’s most notorious member Hugo (alleged wizard and necromancer) added the large underground chamber known as the Goblin Ha’. Tradition had it that he engaged goblins from Hell to build it, hence the name. In truth, although the function of the underground hall seems lost to us, Yester was a substantial stone castle of considerable strategic importance. Slighted by Robert Bruce, the above ground parts were rebuilt over the relatively unscathed Goblin Ha’ in the 14 th and 15 th centuries to provide a robust and somewhat elegant edifice with curtain wall and courtyard .

It was attacked on and off by the English over the next two and a half centuries and was the last East Lothian castle to fall during the ’rough wooing’ of the 1540s. Abandoned in the 17th century, its tall, craggy ruins today are heavily overgrown and shrouded by the surrounding woodland, concealing the still beautiful, relatively intact Goblin’ Ha.

Dunbar Castle

The rock that Dunbar Castle’s ruins now stand on is truly ancient. It was fortified by the Votadini in the Iron Age, by the Northumbrians in the 7 th century, by the Picts soon after, and crowned by a stone castle in the late 11 th century. That final date alone makes Dunbar Castle one of the oldest castles in East Lothian. It was taken by Edward I in the 1290s, and Edward II retreated to Dunbar after his defeat at Bannockburn allegedly pursued by James ‘the Black’ Douglas the whole way (so closely that he was not even able to stop to ‘make water’!). Bruce ordered it slighted, and it was rebuilt stronger than ever before in the 1330s.

The castle was destroyed and rebuilt multiple times throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, attesting to its value as a military target. Finally, in 1884 the construction of a new entrance into Victoria Harbour was completed by obliterating much of the stone outcrop and castle ruins with dynamite.

Bass Rock

This remarkable castle belonged to the Lauder family from the early 14th century, and a curtain- walled castle was built upon it in the 16th century with later artillery defences at the site of the only safe landing place. In 1671 the Bass was sold to the crown and used as a prison for Covenanters, a phase often used as the basis for calling Bass Rock the ‘original Alcatraz’.

Tantallon Castle

Tantallon Castle is something of an anachronism, built after the golden age. Known as the “last of the great curtain-wall castles”, it’s effectively one massive 50ft-tall curtain wall cutting off a promontory jutting out into the Firth of Forth. Architecturally it’s more reminiscent of ancient strongholds like Dunnottar, but it was built in the 1350s by the first earl of Douglas in a time when tower houses were becoming the norm.

Tantallon withstood two major attacks, in 1491 and in 1528. It was modified to better defend against cannon fire, but despite this it

did not withstand Cromwell’s artillery in 1651, and he left Tantallon the ruin that remains today.

Tower Houses

The Wars of Independence had resulted in the destruction of many Scottish Castles by Robert Bruce to deny the English the use of them. In general, instead of new baronial castles on the grand scale of the preceding centuries, the 14 th -16th centuries saw the development of the fortified tower house. This went hand in hand with the evelopment of a royal castles like Stirling which became the seat of the monarch and the centre of government. The old baronial castles were often rebuilt (Dirleton, Dunbar, Hailes and Yester, for example) but the power they originally represented was gathered to the monarch and national government. All eventually were left in ruins. There are many examples of tower houses in East Lothian, some of which were the principal structures of small courtyard castles, and originally 3 or 4 stories in height. For example: Innerwick Castle; Redhouse Castle (near Longniddry); Ballencrief Castle (between Haddington and Aberlady); Garleton Castle; Saltcoats Castle (near Gullane); Stoneypath Tower (near Garvald, rebuilt in the last 30 years and now a private residence); Lethington Tower (now incorporated into Lennoxlove House, home to the Duke of Hamilton); Fenton Tower (now a private residence); Preston Tower (Prestonpans); Auldhame Tower/Castle (near Tyningham).

There is much, much more historical and architectural detail available on all of the fortifications mentioned here. However, this summary purports to be a simplified overview of fortifications in our county.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to David Weinczok for giving me permission to use his material for this summary. The images, barring two of Yester Castle, are from his power point slides and much of the text is his either David’s verbatim or modified by me. I hope that this shortened version still does justice to his talk.

Peter Ramage 29 April 2025

About the speaker

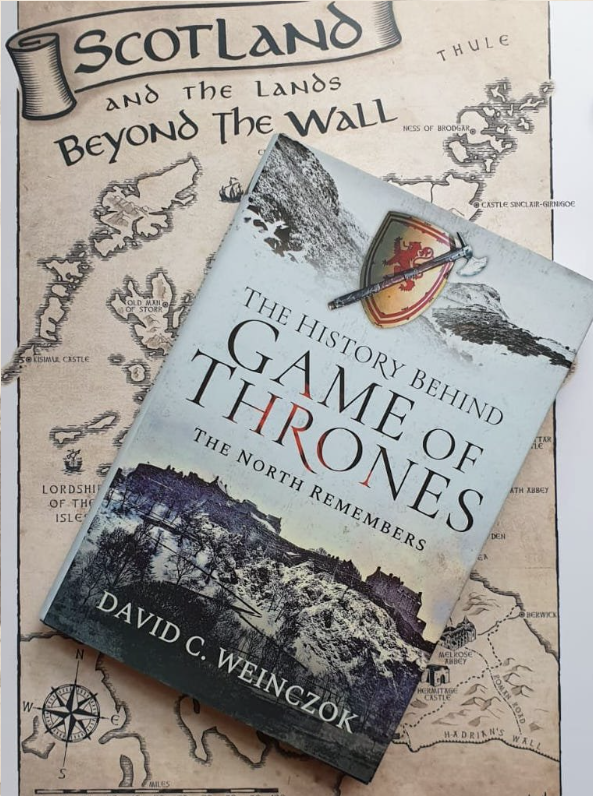

David C. Weinczok is a Scottish historian, writer, presenter, and museums professional. A Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, he has written hundreds of articles for Scottish-interest publications including The Scots Magazine, History Scotland, Hidden Scotland, and The Scottish Banner. David’s 2019 book, The History Behind Game of Thrones: The North Remembers explored the parallels between Scottish history and the world of Westeros.

An avid traveler, he has visited thousands of castles, ancient monuments, and battlefields across Scotland. He is currently writing a creative non-fiction book about six of Scotland’s historic landscapes. David’s specialisms include castles, the Roman invasions of Scotland, the Viking Age, folklore, and the intersection between natural history and human settlements. He is originally from Canada and lives in Portobello, Edinburgh with his partner and dog.

Detail of David’s publications

The History Behind Game of Thrones: The North Remembers. 2019, Pen & Sword Books. Sold in major bookshops and historic sites across Scotland including Edinburgh Castle and Stirling Castle, as well as online direct via Pen & Sword Books and all major e-book sellers. Available in hardback, paperback, e-book and audiobook formats.

You must be logged in to post a comment.