20 February 2025, 7.30 pm at the Holy Trinity Church – Marie Macpherson, Convenor of the Haddington’s History Society

The Scottish Reformation amounted to a seismic change in religious, cultural, social and political life. Nationwide there were pockets of mob violence and military confrontations, but Haddington, home to St Mary’s Kirk, lauded as the ‘Cradle of the Scottish Reformation’, seems to have made a relatively peaceful transition. John Knox, born in the town and attached to St Mary’s during the critical period of 1545 – 1547, was a friend and bodyguard to George Wishart who had been invited to preach at St Mary’s, a seminal event in the development of the Reformation.

Reformist ideas had been around for a considerable time beginning with Martin Luther’s 95 theses, allegedly nailed to the door of All Saints Church in Wittenberg in 1517. Scots scholars commonly travelled in Europe and some brought the Lutheran ideas back to Scotland. One such was Patrick Hamilton who became the first protestant martyr. He was convicted of heresy and burned at the stake in 1528 outside the gates of St Salvador’s College in St Andrews.

Five years later a fellow student, Henry Forrest, was burned as a heretic by James Beaton, Archbishop of St Andrews. Over the period 1528 to1543, as the state and Roman Catholic Church attempted to damp down reforming zeal, there were sporadic executions for heresy and some desecration of Catholic churches in Ayrshire. However, the reformist cause only really began to gather momentum with the charismatic George Wishart. Wishart had returned from Geneva where he had been exposed to the teachings of John Calvin and other Swiss reformers. He travelled around Scotland in 1545 preaching the message of Protestantism but was arrested on the orders of Cardinal David Beaton and tried for heresy. Wishart was burned alive outside St Andrew’s Castle in 1546, his conduct at the event, including his forgiveness of his executioners, essentially lighting the torch for what became a growing fervour to remodel religious practice in Scotland.

The impetus for religious change was further stimulated by the political aims of a number of powerful protestant Lords to break with the longstanding French alliance and French influence on the Scottish polity and develop closer relations with protestant England. Eventually, several of them signed a ‘band’ or covenant (in 1557), including in their number the Earl of Argyll, Earl of Glencairn and Earl of Morton. These ‘Lords of the Congregation’ were later joined by James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, the former Regent. They led the main opposition to Mary of Guise, Queen Regent in Arran’s place. Later they were joined by lords who had been among her most powerful supporters. Finally, following the death of Mary of Guise in 1560, the Scottish Parliament met in August of that year to enshrine Protestantism as the official religion of the country. This was the ‘Reformation Parliament’ which also outlawed the Catholic mass and rescinded all the traditional ties with the Pope.

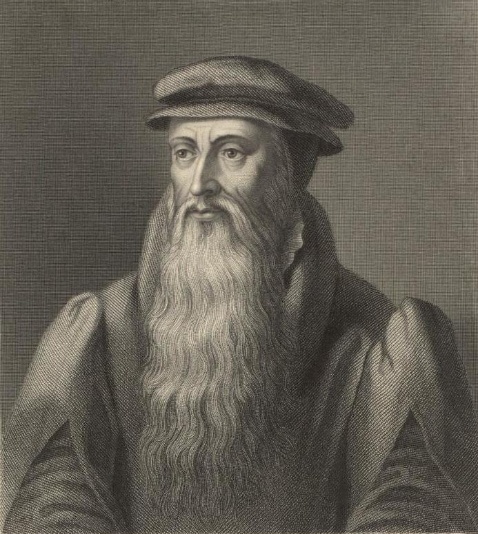

And so, to the role of Haddington’s most famous son – John Knox. His major contribution as the principal religious leader of the Scottish Reformation is well known. Born in Haddington and educated at Haddington Grammar School, he studied for the priesthood at St Andrews where he was greatly influenced by the teachings of John Mair – a great scholar and humanist philosopher widely respected throughout Europe and another East Lothian man. Mair had also attended Haddington Grammar School and carried the soubriquet Haddingtonus Scotus. Knox was ordained as a Catholic priest in 1536. Like many of his fellow students he was appalled by the fate of Patrick Hamilton and this may well have set him on course to become a reformer. He may have refined his great powers of oratory from his close association with George Wishart – himself a great speaker and charismatic emblem of the Reformation. Knox was appointed as a notary apostolic (a church lawyer) working out of St Mary’s in Haddington. He stayed in Samuelston and added to his church role that of tutor to the sons of Hugh Douglass of Longniddry and John Cockburn of Ormiston (both reformist lairds). In December 1545 David Forrest Jr, Provost of Haddington, invited George Wishart to preach at St Mary’s – a chancy business given that Wishart was being pursued for heresy by Cardinal Beaton. Knox became Wishart’s bodyguard, armed with a two-handed sword but Patrick Hepburn 3rd Earl of Bothwell, seems to have intimidated many of the congregation. Thus the turnout was poor and an irritated Wishart cursed the town, suggesting that God’s wrath would bring down war, destruction and plague on the place – rather prophetic given the consequences for Haddington of the ‘rough wooing’. As a guest of John Cockburn at Ormiston it is thought that Wishart might have preached under the great Ormiston Yew but, be that as it may, he was arrested there by the Earl of Bothwell who was currying favour with Cardinal Beaton. Wishart’s execution on 1 March 1546 merely fired up his supporters to the extent that some attacked and murdered Beaton at St Andrews Castle a few months later.

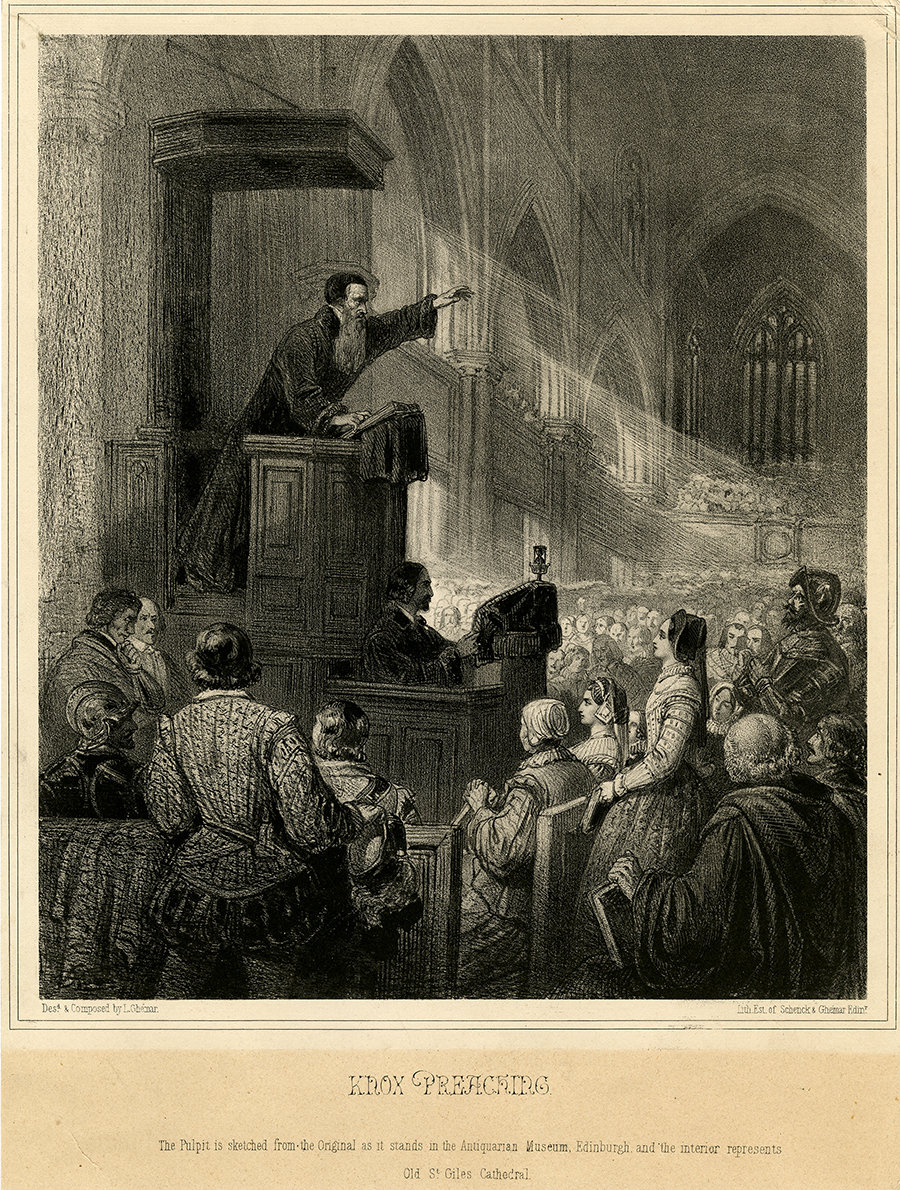

Knox eventually took refuge in the Castle then still occupied by reformers, including Beaton’s assassins. There he (reluctantly) was elected to become chaplain to the congregation, to which he preached a landmark sermon which encapsulated his main tenets for a reformed church. However, following siege by a French army raised by the Queen Regent the occupants – ‘Castilians’ – surrendered and were taken prisoner. Knox was forced to serve as a galley slave in the French galleys involved in the siege, spending 19 months with the oars before his release. After several years of exile, partly in England and partly in Frankfurt and Geneva, Knox returned to Scotland. In 1558/9, a protestant rebellion began. The ‘Beggars Summons’ was pinned to the doors of many Friaries requiring the eviction of all friars with a deadline only a few months thereafter on pain of violent removal. Knox went with a large number of protestant rebels led by the Earl of Glencairn to occupy Perth. After negotiation Glencairn gave control of Perth to Mary of Guise’s army. In attempting to quell the ensuing unrest a boy was shot dead by loyalist troops. Knox then preached an incendiary sermon to a large congregation in the church of St John the Baptist.

The result was mob violence by the ‘rascal multitude’, with the destruction of religious idols and looting of church property, and the same visited upon two local friaries. At this point Lord James Stewart (Mary Queen of Scots half-brother) and the Earl of Argyll, hitherto loyal to the Queen Regent, changed sides and became leaders of the Lords of the Congregation. Power had therefore shifted heavily in favour of the reformists. Later that year Knox gave a similar sermon at St Andrews Cathedral, resulting in more mob violence with the cathedral ransacked and the interior destroyed.

Violent action of this sort, however, occurred only in parts of Scotland, notably Fife, Perth and Ayrshire. As for the rest, including Haddington and the Lothians, there was a gradual acceptance of reform which for ordinary people seemed to partly depend on fear of divine retribution threatened by the likes of Knox, but a lot to do with the novelty of change and the introduction of the vernacular bible. There was no huge enthusiasm, but people in general were happy to welcome change. The establishment of a Presbyterian system, as opposed to an Anglican one, owes much to Knox’s desire to bring the word of God closer to the people and to introduce democratic governance of the Kirk, to which people mostly warmed.

In Haddington itself, there was no real incentive to ransack St Mary’s because it had already been severely damaged during the rough wooing. Although the ‘Lamp of Lothian’ Franciscan Priory had been an extremely rich establishment – excessively grand for what should have reflected the humble values of the Order – it had been burned by the English in 1547. It was finally demolished in 1561. St Mary’s Cistercian Priory, also burned by the English in 1547, was abandoned in 1567 and fell into ruin. No trace of either may be seen today. Some remains of the ‘leper church’ at St Laurence survived until 1906. The shell of St Martins Kirk is Haddington’s oldest standing building, a survivor of partial demolition in the Reformation.

Until 1560 the town council was responsible for the establishment and upkeep of churches and their associated priests. After the Reformation the congregation through their Presbyteries elected ministers and provided for them. In Haddington, as for the most part elsewhere, many of the Roman Catholic clergy converted and continued to preach, now as Presbyterians. There was a general acceptance of this and little animosity shown towards them by the general populace because most were from local families. Memories of the difficult times for Haddington in the ‘Rough Wooing’ only 15 or so years before may have suppressed any urge towards further upheaval and destruction in the town.

Of the major players at the time with local interests we must include William Maitland of Lethington – Secretary Lethington to Mary Queen of Scots.

An astute politician and a reformer he nevertheless resisted the implementation of Knox’s plans for the reformed church as set out in the ‘First Book of Discipline’ and helped to ensure that much of the moneys, lands and valuables of the pre-reformation churches and religious houses was distributed to the Crown and the powerful Lords. Knox’s intention had been to use a large fraction of it to support the establishment of the reformed church, pay for parish-based schools for all, university education and poor relief. In the end barely a third of the wealth was available for this, resulting in poorly paid ministers, an underfunded church and the abandonment of the full education programme.

Nevertheless, the Presbyterian church became firmly established in Scotland and so was able to withstand the efforts of the Stewart kings in the 1600s, in particular Charles I, to impose an Anglican system and to survive the ensuing religious wars of that century.

Peter R 26/02/2025

You must be logged in to post a comment.