21st November 2024 – Steven Veerapen, Historian and Author.

Witches: A King’s Obsession

Daemonologie: the Scottish Witch Hunt of 1597 and its Legacy

Dr Steven Veerapen gave a lucid and entertaining talk on the origin, development and legacy of James VI’s obsession with witchcraft as a major source of evil and misfortune in Scotland. Against a background of acceptance of witches by society at large, and by the king himself originally, where witchcraft was not considered to be a serious issue, the question arises of why the sudden change in the 1590s.

James was ruling in politically turbulent times, facing threats from various conspiracies. A principal organiser of these was his cousin Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell. Things began to gel in James’ mind with the storms in 1590 which delayed the sea crossing by his betrothed, Anne of Denmark. The suggestion that witchcraft was being used to try to prevent the marriage originated in Denmark, and James took this to heart. Responsibility was attributed to a number of East Lothian women who were accused of dealing with the devil in North Berwick kirk to raise the storms. After a series of trials by the king at Holyrood in 1590-91, they were found guilty of witchcraft. James was becoming increasingly paranoid, encouraged by treasonous acts against him and convinced himself that witches were plotting against his life. Indeed he saw Bothwell as the witch general and later had him accused and tried.

However, as a skilled self-publicist, James saw a way to make political capital from these events. He knew he was heir to the throne of England and that Elizabeth I, despite the views of her more hard-line ministers, did not consider witchcraft to be a threat to her realm. The English Witchcraft Act of 1562 allowed for the execution of witches only if they could be proved to be responsible for a murder. Otherwise, those found guilty of witchcraft could expect to live but be imprisoned or suffer minor punishments. There were no witch-panics in England at this time. It was the view of some, probably including James, that there were very many witches in England and that they mostly went unpunished. This was down to Elizabeth’s ambivalence which, in James’ view, suggested she was not sufficiently learned to grasp the true dangers, as he saw it, of witchcraft.

Hence James commissioned a report on the so-called North Berwick trials, positioning himself as the central hero, in a pamphlet entitled ‘Newes from Scotland’. Most likely the article was written by the religious zealot James Carmichael, minister of Haddington. The pamphlet was published in London and assuredly promoted James as God’s chosen for the English throne.

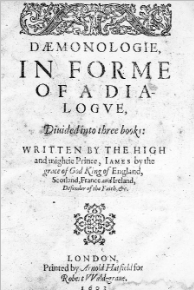

James very much saw himself as a leading light in the understanding of demonology and applied himself to the preparation of a philosophical and practical guide to the nature, identification and dangers of witchcraft. His book ‘Daemonologie’ (first published in 1597) drew on a number of sources, for example:

- pamphlets published on the execution of witches in England;

- ‘Malleus Malificarum’ (published in 15th century);

- ‘The Discoverie of Wichcraft’ by Reginald Scot (1584).

While the latter did not align with James’s belief in the reality of witches, indeed it was a firm rejection of the existence of witches and witchcraft, James reversed and adapted to his own ends many of Scot’s examples.

James hoped that through ‘Daemonologie’ he would be seen throughout Europe as a learned forward thinker, fully in tune with the religious and social mores of his time.

The book itself set out a hierarchy of Satan’s recruits, those in the top tier having personally met with Satan and made a Faustian pact with him, and those in the low tier seen as Satan’s slaves who fall within his thrall because they see this as a way of compensating for the vicissitudes of their lives. The latter often, although not always, tended to be the poor and deprived at the lower end of society. James’s view was that all magic came from Satan, that curses would work only if Satan wished them to. He saw such things as wax or clay images, poisons, perceived occult powers all as evidence of Satan’s work.

A central idea was that witches held meetings (conventicles) to make plans and to worship their master. James addressed the issue of travel: how witches get together for meetings. To us the bizarre ideas of travel in a sieve over water, flying through the air or astral projection (sending one’s spirit but not body) were acceptable then. These were widely held superstitions, not at all original, but that travel through the air could only last as long as the witch could hold their breath originated with James.

There was a view that some people who appeared to be witches had nothing to do with Satan and that they were simply mad. How could you tell the difference? James’ answer was that mad people were solitary in their madness – did not meet in groups – whereas witches did! In this context he discounted the idea of werewolves as Satan’s work because they were solitary and were probably just mad humans.

How may a witch be identified, then? There were a number of approaches:-

- confession (the ‘gold standard’ of proof) – obvious flaw relates to how such a confession obtained;

- ‘devils mark’ – wart, blemish, cast in the eye, insensitivity to pain ( very much what the investigator wanted to define);

- accusation by an already confessed witch.

Altogether rather creaky ‘evidence’ in a modern law court !

In 1596 James again saw treason in the air when an Edinburgh mob assailed the building he was in. Presbyterian preachers had convinced the populace that James was too Catholic in his religious outlook and was planning an alliance with Spain which would have consequences for the reformed church. Clearly there was a major rift between Kirk and Crown which James needed to close. Recognising witches as a common enemy the two sides were reconciled sufficiently to cooperate in the massive national witch hunt of 1597.

This began in Aberdeenshire and moved gradually south. People increasingly began reporting witches, 85% of those accused being women. Demands for government commissions to investigate witches accelerated and accusations ballooned. Among the first to suffer and be executed were

Isabel Strachan – charming a man to stop him from beating his wife;

Jane Wishart – causing a still-birth, spoiling ale and casting spells using body parts of hanged man.

And so on. Many met similar fates on the basis of charges like these.

Notorious at this time was one of the methods used to distinguish between the innocent and guilty: identification by a confessed witch. One Margaret Aitken of Balwearie was found to be a witch and, in exchange for her life, she offered (or was invited to offer) to be carted from town to town to identify the true witches in groups of accused folk, largely women. Many executions followed. However, doubt on the veracity of this approach began to grow and, in Glasgow, the authorities found her out. A woman identified as a witch in one group of women was included in a new group. Margaret failed to identify her this time. Margaret was executed towards the end of 1597. Following this witch hunting declined sharply and only occasional individual incidents occurred. When James moved south in 1603 as James VI and I, although he was still convinced of the dangers of witchcraft, he did not consider England to have a witch ‘problem’ and witch hunts there only began after his death, and later in the 17th century.

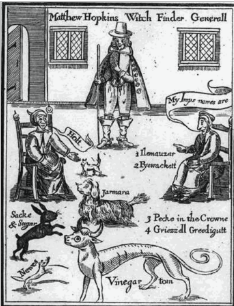

‘Daemonologie’, however, remained a primary reference for the next hundred and fifty years or more for the identification and prosecution of witches. There were occasional regional witch panics in England, with self-proclaimed witch finders leading the persecutions. Notorious among them was Matthew Hopkins, self-proclaimed ‘Witchfinder General’, who operated during the civil war mainly in East Anglia. His methods are described in his book ‘The Discoverie of Witches’ (1647), which clearly owed much to ‘Daemonologie’.

The Salem witch trials in Massachusetts in the 1690s relied on the guidance of James’ book, in particular invoking evidence of spectral transmission. The false testimony of a number of young girls led to the arrest of over 200 individuals, mostly women, the conviction of 30 individuals and the execution of 19.

Eventually, witch hunting died down and effectively ceased. Generally this was because people were becoming increasingly sceptical of the type of evidence used and how it was obtained. The empirical rationalism of the Enlightenment in the 18th and early 19th centuries finally consigned witch trials to history.

Hence for nearly 200 years, ‘Daemonologie’ was at the heart of the sorry persecution of folk accused of witchcraft. Most of the accused were women, although some 15% were men, all mostly from the margins of society. Why women? The perception then, voiced by James himself, was that women were the weaker sex, were less rational and so more susceptible to the blandishments of the devil. Interestingly, persecutions were not sectarian: Roman Catholics and the various flavours of Protestantism offered victims, and Roman Catholic and Protestant polities took a very similar stance on the matter of witches.

Peter Ramage November 2024

You must be logged in to post a comment.