17th October 2024 – A talk by Cameron MacLean, Numismatist, 7.30 pm at the Holy Trinity Church

(With thanks to Cameron McLean for permission to use his images in this summary)

Cameron McLean of Glasgow University introduced the topic and then spoke on a series of coins, mostly from the Lord Stewartby collection, to cover the period from the first minting in the reign of David 1, to the last following the Union of Parliaments. They reflect something of the historical events between the 1130s and 1707.

Ian Stewart, later Baron Stewartby (1935 – 2018) began his professional life as a banker, but then moved into politics in 1974 as a Conservative MP. He occupied several ministerial posts under Margaret Thatcher, the last being Minister of State for Northern Ireland. In 1991 he was given a life peerage and served in the House of Lords until 2015.

Through his interest in Scottish coinage, he became a respected numismatist early in life, having written as a teenager ‘The Scottish Coinage’, still a valued reference book today. He continued to publish in numismatics throughout his life. Stewartby’s collection was made over about 70 years his interest piqued in 1941 when, as a young boy, he noticed a ‘bawbee’ (6d piece) on a shopkeeper’s counter carrying the heads of William and Mary, dated 1694.

From then he steadily accumulated a collection of Scots coinage amounting to several thousand by 2010. This represented the largest collection of Scots coins made by a private individual. Sadly, part of the collection (over 1000 coins) was stolen in 2007 and has not, to date, been recovered. A reward for its return stands at £50,000, reflecting something of the value of the loss – £500,000! Shortly before his death in 2018 Lord Stewartby gifted the remainder (about 6000 coins, roughly ¼ of all extant Scots coins) to the Hunterian Museum, University of Glasgow.

Cameron then took us through his selection of coins, looking at significant aspects of their design and manufacture as it changed over the centuries. He outlined the early technique of producing coins by hammering them out from metal blanks or sheets (silver, gold, copper or copper alloy) using engraved iron dies – the origin of the term ‘struck’ in relation to coin production.

The top photograph shows the pattern of one side of a coin engraved into an iron die, and the resultant coin hammered out from it. The top and bottom dies are each engraved, one with the obverse face and one with the reverse face (shown above). The lower photograph with ‘mushrooming’ of the smaller die shows the effects of repeated hammering. The skill of the artisan engraver is obvious. Hammering was succeeded by the more efficient screw press and the rocker press in the 16th century.

Coins were both currency and symbols of political power. Commonly a representation of the king’s head with Latin inscriptions (often abbreviated) are found on the obverse side (‘heads’), while heraldry and, other symbols and Latin inscriptions are found on the reverse side (‘tails’). There are variations, but the monarch’s name is always engraved on the obverse whether with image or not. Each of the following pictures of coins show the obverse on the left. Values are Scots, occasionally with sterling equivalents.

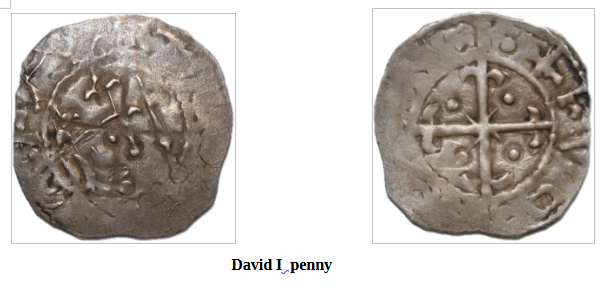

David I instituted Scots coinage during his reign, with the first silver coins. They are extremely rare and the example here is a silver penny from the collection of W J Cuthbert, any collected by Lord Stewartby being among those stolen in 2007.

David I penny

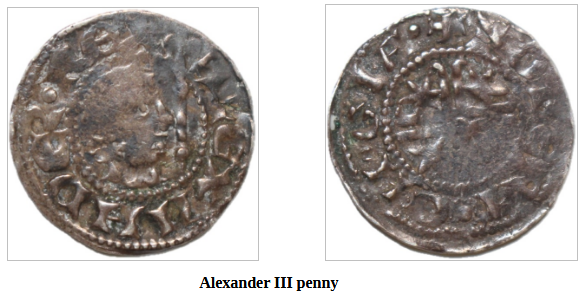

These were minted by ‘Hugo of Roxburgh’. David also established mints in Carlisle, Berwick, Edinburgh and Stirling. Later, Alexander III authorised a mint in Glasgow which operated for a short period 1249-1250. The example here is an Alexander III penny minted by Robert of Glasgow.

Alexander III penny

After the death of Alexander and the Wars of Independence in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, King Robert Bruce coins were struck, of which this very rare penny is an example.

Robert I (Bruce) penny

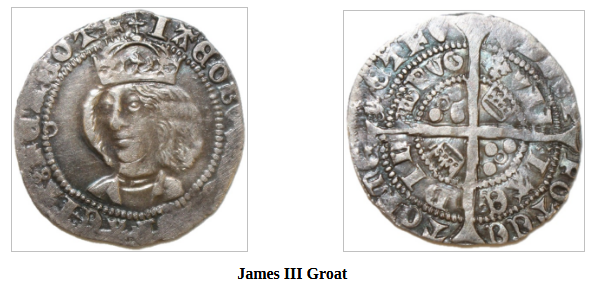

By the 15th century the skill of the engravers was such that much more lifelike monarchs’ heads were produced, as this Edinburgh minted 1484-1488 James III groat (6d) shows.

James III Groat

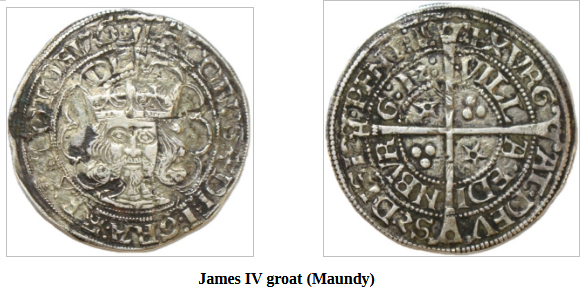

Similarly, the 1512 Maundy Money coin of James IV displays a well rendered face with beard. The coin will likely have been handled by the king himself. What an interesting thought that the hands of 20th and 21st century Scots have in this indirect way touched the hand of our 15th century Renaissance king.

James IV groat (Maundy)

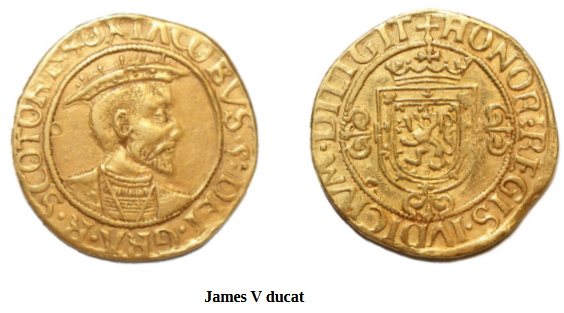

The James V ducat (£2) 1540-142 is an example of the earliest coin minted from Scottish gold

James V ducat

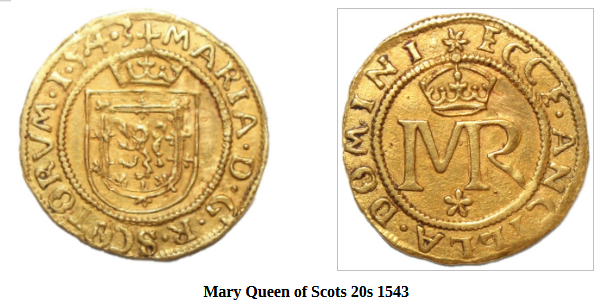

After James’ death in December 1542 his infant daughter, Mary, succeeded to the throne at 6 days old. This and her subsequent career produced a number of coin design changes as she moved from one phase of her life to the next. The first coin of her reign, struck in 1543, had no portrait. It bears a small cinquefoil beneath her monogram, the device of her regent, the Earl of Arran.

Mary Queen of Scots 20s 1543

The first coin struck with Mary’s portrait was in 1547, and in 1548 she sailed to France as the betrothed of the dauphin, Francis. In 1558 they married and in 1559 Francis succeeded to the throne. Mary was thus Queen of Scots and Queen Consort in France. Her mother, Mary of Guise, had replaced Arran as her regent in Scotland. The coinage reflects these arrangements, with Francis and Mary coins struck in 1558, the example here being a testoon (5s)

Mary and Francis testoon

Note the addition of the Cross of Lorraine on the reverse, and the cross lying behind the shield on the obverse. These are the devices of Mary of Guise.

On Francis’s death in 1560, Mary prepared to return to Scotland and had French artisans design the dies for her first coinage as Queen of Scots in her own right. The testoon here was minted in Edinburgh in 1561.

Mary Queen of Scots testoon

In 1567 Mary was forced to abdicate and her son James succeeded as James VI. In 1575 a gold £20 piece was minted – at 30.5g the heaviest gold coin ever circulated in Scotland. Only 20 now survive.

James VI £20

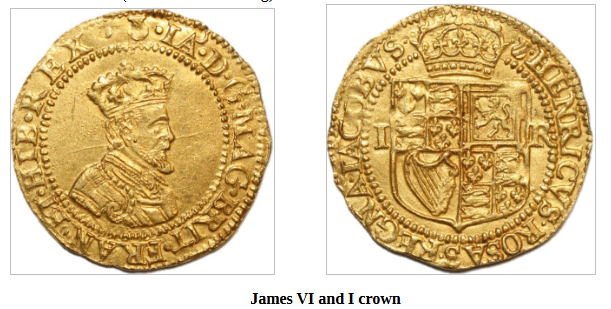

With the Union of the Crowns in 1603, the coin design changed again. Soon after, parity of exchange between Scots and English currencies was established at £12 Scots = £1 sterling which facilitated the use of coins in both countries. Thus the following example of a Scots crown (£3 Scots or 5s sterling) from 1605-1609:

James VI and I crown

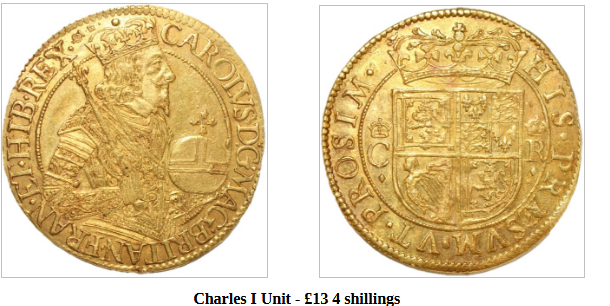

The introduction in the reign of Charles I of machinery to produce milled coins greatly improved quality and uniformity, and the milled edges made it impossible to ‘clip’ them without detection. (Clipping was the illegal removal of small slivers of silver or gold from the edges of coins to acquire a stash of precious metal which could be melted down and sold on).

Charles I Unit – £13 4 shillings

The last Scots gold coin was minted in 1701 towards the end of the reign of William III. Known as a pistole (£12 Scots), these are extremely rare in the modern collector’s market.

William IV pistole

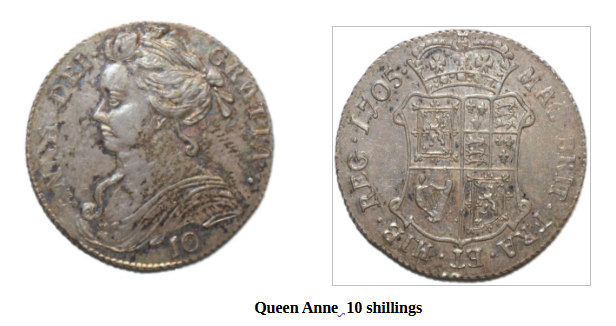

The last Scots coins were minted during the reign of Queen Anne, of which the following 10 shilling piece is an example.

Queen Anne 10 shillings

After the Act of Union in 1707, currency was standardised across the nation. Mints in Edinburgh and London produced the same coins of which the following Queen Anne crown is a good example.

Queen Anne crown 1707

The Edinburgh and London mints were stadardised to use the same designs at this stage, and the coins minted in both locations were essentially identical. This example of the reverse face of the Queen Anne crown is a good illustration.

Edinburgh London

The last coins to be minted in Scotland were produced in 1709.

In conclusion, the complex history of Scotland is reflected in the changing coinage over the six centuries from the mid-1100s to the union of 1707. Thus ended Cameron’s erudite and interesting review of Scots coinage through the lens of the Lord Stewartby collection. Time for questions raised the issues of coin debasement (reduction of precious metal content), use of foreign currencies (as when a French army was present in the mid-16th century), clipping, and the early approach to producing half-pennies and farthings by cutting penny coins into halves or quarters.

Peter Ramage 20/10/24

You must be logged in to post a comment.