A talk by Dr Coralie Mills of Dendrochronicle – 5th September, 7.30 pm at the Holy Trinity Church

In a very interesting and absorbing talk, Dr Coralie Mills, founder and Director of the consultancy Dendrochronicle, described the extent and significance of work on historical timbers to establish the geographical origins of the wood and likely dates for the age and felling date of the source trees. Her particular interest is in native oak in south-east Scotland where she is much engaged in the South- East Scotland Oak

Dendrochronology (SESOD) project. In Scotland only about 50 site investigations where oak structures are found have been commissioned so far, compared with many hundreds in England and Wales. While most of the Scottish sites are in the west and south-west, the south-east includes a number of ecclesiastical, military (castles), municipal and some vernacular buildings. St Giles Cathedral, Kirkliston and, of course, St Mary’s in Haddington are among the churches. Stirling and

Neidpath castles are also notable study sites, while Jedburgh Town hall, George Heriot’s School and 42-44 Market Street in Haddington represent municipal and vernacular buildings which contain timbers of interest. The Old Bridge at Ancrum is another site where old oak components are under investigation. Elsewhere excavations of old timbers from crannogs, wells and other long buried structures have yielded fascinating insights into the age and origin of timbers uncovered.

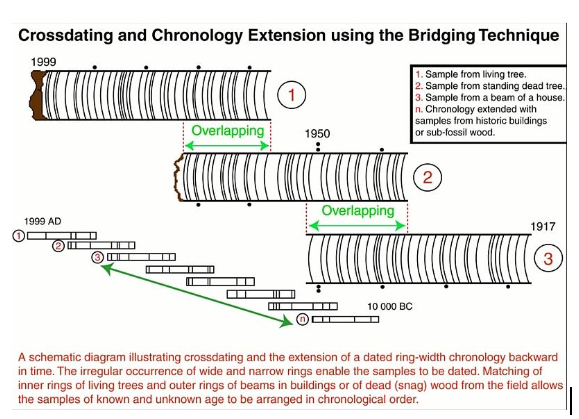

Dendrochronology is basically the determination of the age of a tree or a piece of timber by counting the number of annual rings visible in a cut section or core. This provides the most precise physical dating method available to archaeologists, capable of yeilding the exact year in which the tree was felled. Tree rings vary in thickness according to the climatic conditions pertaining at the time. For example, in a warm spring and summer the more rapid growth produces relatively wide rings, while if a growing season is relatively cold or dry rings will be significantly narrower. Thus, in the wood of a 300 year old oak, say, the 300 rings will form a pattern of wider and narrower bands which will occur in the same sequence in all of the oaks growing in that region. This ‘bar code’ is the basis for the construction of a dating sequence extending backwards in time by matching overlapping ring patterns in successively older woods – see diagram below.

For the SESOD project the old living oaks in Dalkeith Park were used to establish a reference chronology from 2010 to 1569. This can be extended further back in time as old oak timbers with overlaps are identified. However, this has proved to be a challenging task, with significant gaps remaining in the 13 th and 15 th – 16 th centuries.

That a complete 1000 year sequence for SW Scotland was obtained in the early 1980s using only 6 locations, reflects the relative abundance of native oak timbers derived from these sites in that part of the country and surviving old oak trees. In comparison with other parts of the country, SE Scotland has suffered in greater measure from the frequent wars with England in the first half or so of the last millennium: destruction and burning of buildings, vernacular buildings in particular,

displacement of people, and scorched earth policies. The latter, combined with overgrazing by sheep, limited woodland regeneration. All of these contribute to the dearth of native oak data in this region. Hence the main thrust of the SESOD project, the objective being to close some or all of the gaps in the SE Scotland oak dendrochronological record over the last millennium by identifying relevant native oak in the study sites mentioned earlier.

Native oak was in increasingly short supply here from the mid-15 th century when imported Norwegian oak and Scandinavian pine became important, the latter beginning to dominate as Norway began to restrict the export of oak. The eastern Baltic was another source of imported timber, eg. oak from the Gdansk region, pine from Karelia. All dendrochronological data is routinely digitised, and computer searches of databases, in this case Norwegian, Polish and Finnish data, are used to match newly analysed timbers to their place of origin. For example 18 th century pine from timbers in Fort George and in the 42-44 Market Street house in Haddington originated from the eastern Baltic; painted boards and beams in the Queen’s bedchamber at Stirling Castle used Scandinavian pine. Norwegian oak felled in 1670 is found in George Heriot’s School; Norwegian oak sled runners form part of a structure in Abbey Strand, Edinburgh; Neidpath Castle upper floor timbers are of

Norwegian oak. In many old buildings there is considerable evidence of re-use of oak and pine in repairs or new construction. Kirkliston Parish Church is a good example where native oak felled in 1203 has been reused. St Giles Bell Tower was constructed from native oak, but this came from the Royal Forest of Darnaway in NE Scotland sourced from 300 year old trees felled in 1453/4 and 1459/60. Native oak in Jedburgh Town House and the lower floors of Neidpath Castle seem to meet the

needs of the SESOD project, as may those in Ancrum Old Bridge.

So, what about St Mary’s Parish Church in Haddington? Can it provide oak of the right age and provenance? The answer is that it might, eventually. The nave roof is supported by about 45 timber trusses (see photo) consisting of rafters, beams, struts etc. These are constructed from a complex mixture of timbers, some obviously reused, and many repurposed. The species are pine and oak, and core samples have been analysed for some of the wood. The reused oak components have often been reworked, some showing clear signs of weathering (inferring exposure to the elements for a time), and some rafters show multiple nail holes, hence in previous use they may have carried cladding or, if turned over, sarking. Some braces show redundant mortise slots. Two distinct sets of carpenters’ marks are evident. Dendrochronology results so far indicate that some oak planks originated from trees felled in the Gdansk region around 1400-1410, and could conceivably have been part of the original structure since construction of St Mary’s began in the late 13 th century, the church consecrated around 1410, and completed later that century. This unusual provenance may reflect the presence of a Scots settlement in Pomerania from the late 14 th century. Also, one of the rafters is of Norwegian oak felled in the late 15 th century. As yet native oak has not yet been found, but the results so far indicate that the St Mary’s study is likely to provide an important contribution to the SESOD project.

Finally, Coralie made the important observation that we should be taking much greater care than hitherto in the regulation of our timber heritage, both woodland and structural. Its value in an archaeological and historical context through dendrochronology was so clearly illustrated by Coralie’s talk.

Members can find out more about Coralie’s fantastic work at dendrochronicle where you will find numerous useful resources and events planned for the future.

You must be logged in to post a comment.