A talk by Bryan Hickman was held on 18th April 2024 at the Holy Trinity Church, Church Road, Haddington. The talk described the standing remains of the 12th century churches that can still be seen in the Lothians.

The following is a summary of his talk:

Brian first painted in the background to Norman influence in Scotland, in particular the role of the close relationships forged by David I, both before and after he ascended the throne in 1124. As a young prince, David spent much time in the Norman court of Henry I, and from this he carried forward many Norman ideas to Scotland during his reign. He introduced, for example, the feudal system, burghs/market towns, and the parochial system. He reorganised religious practice in Scotland to conform more closely with that of England and continental Europe, completing the move from the Celtic to the Roman church. He founded abbeys and invited the Templars to Scotland, together with notable Anglo-Norman families. The latter were given lands in exchange for military and political support and, consequently, were responsible for the construction of several castles and for many churches. The links with Norman England were strengthened by the marriage of David’s daughter Matilda to Henry I and the marriage of his only surviving son, also Henry, to Ada de Warrene, later Countess of Northumberland.

Brian reviewed the remains of Norman churches, moving from east to west across Lothian. Most, if not all, date from the 12th century and some may have been built on the sites of earlier churches. The remains of many have been preserved as parts of more recent, often Victorian, churches. Sometimes the Norman masonry is almost completely obscured. Evidence from church design and carved motifs strongly support the view that the same team of 12th century masons was involved in the construction of many of them. The general plan seems to be a variant of a cellular model to include apse, chancel and nave. A square tower may have been included in many cases, but these could be relatively unstable, with a tendency to collapse, and the originals do not always feature in the remnants seen today. Also, the transepts, typical of much church architecture, were often absent. In later times, aisles were sometimes constructed on the north or south sides.

The classic Norman architectural features include a variant of the Romanesque arch, cushion capitals, and wall-head corbels (often carved into grotesque heads of one kind or another).

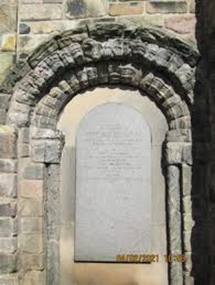

St Baldred’s Tyninghame

The ruins are sited in the grounds of Tyninghame House and were excavated and ‘tidied up’ with some rebuilding in the 19th century to create a folly and burial ground for the Earls of Haddington. Although roofless, the arches through which the chancel and apse were accessed remain, showing the characteristic semicircular profile with roll/zigzag mouldings and supported by sturdy pillars. The nave is represented by its foundation only. (See photo above)

St Martin’s, Haddington

This church may well have been the principal place of worship for the nuns of the Abbey of St Mary’s, founded by Countess Ada in 1158. Only the roofless shell of nave and chancel with buttresses remains, showing the deeply recessed windows and decorated semi-circular door and window arches typical of a Norman church. There is no above-ground evidence suggestive of an apse or tower.

St Andrew’s, Gullane

Constructed in the second half of the 12th century, with later additions, the ruin consists of a nave and chancel with the later aisle. The chancel doorway has been built up, but the arch is still clearly visible.

St Mungo’s, Borthwick

The church was in continual use until the 18th century when it burned down. It was rebuilt in the 19th century incorporating some of the original structure. The most obvious part is the semi-circular apse with its Romanesque window arches, the rest of the rebuilt church showing the pointed arches of the gothic revival.

Duddingston Kirk

Constructed in the first half of the 12th century, the original church consisted of a square tower, nave and chancel. Today only the south wall remains of the original, forming part of the modern kirk. The original south doorway is blocked off, but the Norman arches with their chevron designs and supporting pillars with cushion capitals are still visible. So too are the Norman wall-head corbels beneath the chancel eaves.

Other Edinburgh Churches

St Giles Cathedral was originally of Norman construction, but no Romanesque architectural features remain. There is a 19th century woodcut engraving of the original Norman north door with the carved semicircular arches and pillars.

Holyrood Abbey, founded by Augustinian monks in 1128, retains Romanesque elements but the remains are mostly of Gothic character.

St Margaret’s Chapel in Edinburgh Castle may well be a remnant of a much larger structure. It is a 2-cell building now, consisting of a chancel and apse. The chancel arch and cushion capitals are clearly Norman.

St Cuthbert’s, Dalmeny This is the best-preserved Norman Church in Scotland, probably founded by a member of the Norman Gospatrick family. Originally it was constructed as a 4-cell church in the second half of the 12th century, but the tower collapsed around 1400. In 1937 a replacement tower in keeping with the original architecture was added.

Other Lothian Churches

Kirkliston Parish Church, prominent on a hill, retains the Norman south door. and a tower to which a belfry was added in 1687.

Ratho Parish Church has the remains of a Norman south door. It is a 2-cell building to which an aisle was attached in later times. There is no visible evidence of other cells.

Kinneil Parish Church, near Bo’ness, is again a 2-cell church with later aisle.

Abercorn Parish Church is much altered from the original. The Normans built a new church on the site of a predecessor dating from the 7th century. It has a remnant of the original Norman door. In the 19th century a new Romanesque arch and door were constructed.

St Nicholas Church, Uphall, is a 3-cell building consisting of tower, nave and chancel to which the later Houston aisle was added.

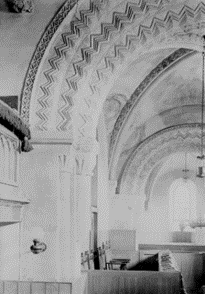

Dunfermline Abbey

Finally, Bryan included Dunfermline Abbey because of its general importance in the 12th century when Dunfermline was the principal town in Scotland. The remaining Norman sections are the chancel, transepts with tower, and nave. The nave is buttressed and, internally, has highly decorated Norman arches supported by massive, decorated piers.

Peter Ramage

You must be logged in to post a comment.