by Victoria Brown (Education Manager, National Mining Museum, Newtongrange) – 16 March 2023

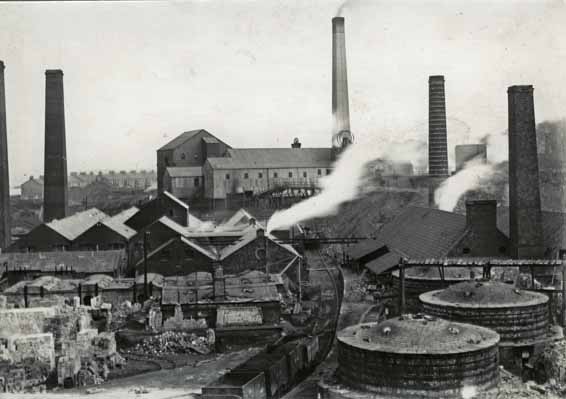

Victoria began by outlining the huge scale of the Scottish coal mining industry. At its peak, in the first half of the 20th century, it employed about 150,000 people and made a major contribution to the British economy, supplying coal for industry (ovens, kilns, blast furnaces, power stations, chemicals, etc.), transport (steam engines, shipping) and domestic use (heating, coal gas) and for export. The Lady Victoria (1895-1981) in Newtongrange, formerly a large and very productive Midlothian colliery, is now a museum and education centre dedicated to the history of coal mining in the Lothians.

Historically, the development of coal as an important resource in the east of Scotland seems to have begun with monks digging it as a fuel for kilns and for salt panning. The first mention of coal was in a charter of 1291 granted to the religious communities of Dunfermline, but it was apparently first worked systematically by the monks of Newbattle Abbey.

The coalfield they exploited is the Midlothian (Esk Basin) coalfield which extends roughly from Gorebridge and Penicuik in the southwest to Portobello and Longniddry in the northeast. Coal is found in many layers (seams) within the Carboniferous sedimentary rocks, sometimes breaking the surface along the northwest and southeast edges of the basin. Seams extend northwards and are continuous with those of the Fife coalfield, hence mine shafts from a number of collieries extend northwards under the Forth. The East Lothian coalfield is found in the west of the county, a geological extension of the Midlothian field and much smaller in area.

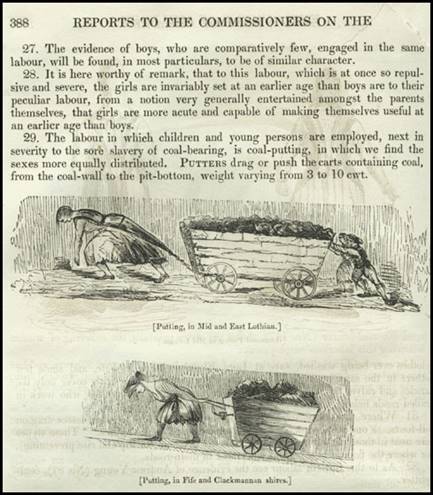

With the recognition of coal as a very important industrial resource from the 17th century on, coal mining became the concern of big landowners. Coal was used locally to fuel the ovens for salt pans, and the kilns for the manufacture of glass and ceramics. Much coal was also exported. The owners developed collieries as major commercial enterprises and became extremely rich in the process. This was on the backs of the sweated underground labour of men, women and children (from the age of 5). For about 100 years from 1606, workers were legally bound to their masters – essentially as serfs, with no right to leave the job for something else without the express permission of the owners. They worked very long hours under the most backbreaking, dirty and dangerous conditions. This was as true of the East Lothian collieries as of the much larger ones in Midlothian, Fife and elsewhere in the UK. These conditions of work continued until well into the 19th century. Growing public disquiet, especially after the loss of 26 children drowned in the Huskar Pit disaster, 1838, in South Yorkshire, led to the establishment of a Children’s Employment Commission. It published a report (1841/42) based on extensive interviews with colliery owners, managers and workers of all ages. Victoria read examples of the statements of an 8 year old boy and a 17 year old woman who worked at Elphinstone Colliery which graphically illustrated the conditions under which they worked. The immediate result of the report was that, from 1842, children under the age of 10, and women, were banned from working underground (although, to avoid depleting limited family incomes, some tried to evade the ban).

Colliery workers constantly faced the prospect of injury and illness – common hazards of the job. Accidents were regularly fatal. On occasion major disasters occurred in which many miners lost their lives. Most commonly these resulted from the presence of dangerous gases in the mines – ‘blackdamp’ ( an asphyxiating mixture of carbon dioxide with limited air), and ‘firedamp’ (the highly flammable methane). In 1877 one the worst disasters in mining history resulted from a methane explosion at a Blantyre Colliery. Victoria presented the appalling statistics: 207 men killed, leaving 92 widows, and 250 children fatherless. The youngest of the dead was 11. In the same year there was an explosion at Prestongrange Colliery which killed 2 men and a boy. These were two examples of many, nationwide, until the advent of safety lamps greatly reduced the incidence. The Mines Act of 1911 further enhanced safety by requiring ventilation/emergency exit shafts and specifying that all pits employing over 100 men had to employ at least 5 specially trained rescue miners. Most collieries still in operation in 1947 were taken over by the National Coal Board. The coal industry remained a major employer for several decades but, gradually, it became uneconomic and most collieries were closed by the late 1980s.

Over the period covered by this summary, several collieries operated in East Lothian, for example:

Fleets (Tranent) 1799-1875 – one of the Tranent area collieries known for its links to the development of the Tranent/Cockenzie Waggonway

Gladsmuir/Penston (closed 1762 after only a few years of operation – 13 workers)

Elphingston

Pencaitland (Woodhall)

Prestongrange (earliest recorded colliery – worked by the monks of Newbattle Abbey)

Prestonlinks.

In 1947 only 6 East Lothian Collieries were adopted by the National Coal Board and employment in coal mining reached its peak in East Lothian in 1948, with 3000 workers.

The biggest employers (several hundred workers each) were Prestongrange and Prestonlinks which closed in 1962 and 1964 respectively. The former was re-incarnated as Prestongrange Mining Museum. The latter was completely cleared to make way for Cockenzie Power Station (now also cleared). The last major coal mining enterprise was the Blindwells Opencast operation, which supplied coal to Cockenzie Power Station, and which closed in the 1990s with land restitution completed by 1998. It is now the site of Blindwells new town.

Peter R

19/03/2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.